Jun 13, 2013

by Con Chapman

There is a charity in Boston that helps the homeless by publishing a newspaper to which they contribute articles and poems. The thinking is that if a panhandler has a newspaper to sell, as opposed to merely asking for a handout, people will be more likely to give him or her money. As a happy byproduct of this retail transaction, the theory goes, the downtrodden will acquire valuable skills by cranking out content for the good sports who fork over cold, hard cash for their efforts.

What a great idea; help people get out of poverty by turning them into freelance writers. While we’re at it, why don’t we take away the deposit cans and bottles they’ve been collecting?

As someone who first sold a freelance article for $100 thirty-five years ago (adjusted for inflation: $3.26), and worked the better part of a summer to get it, all I can say is if you want to lift people out of poverty freelance writing is as good a tool as any, if by “any” you mean maypole dancing.

As a freelance writer, you deserve to be treated like the professional you are, although with pay for print articles being as low as it is, you may feel like you’re preserving your amateur status for some future Freelance Olympic Games in Oslo, Norway.

I sold thirty-five freelance articles in 2012, my best year ever. At the everyday low prices that prevail in the marketplace for unsolicited non-fiction, my take-home pay averaged twenty cents a word. Not bad, you think. You’ve got plenty of words—you’re the freaking Wal-Mart of words, fer Christ sake! The problem is, no one wants to buy the Big Gulp size; everyone wants to buy the little, teensy 430-word sip.

And then there’s the phenomenon of reverse literary panhandling. One editor to whom I sent the taboo-breaking article “How to Tell Your Teenaged Son From a Dead Rodent” went out of his way to tell me how much he enjoyed it, and how eager he was to run it in his suburban weekly. “Of course, I have no budget for freelance articles,” he added with a fraternal tone, as if an experienced writer like myself would know that one doesn’t actually get paid for this sort of thing.

“Mais oui, mon ami!” I replied with the devil-may-care attitude of a blase, sophisticated boulevardier et flaneur, like Maurice Chevalier. “Why should you pay me for something that will mean so much to your readers, when it is but a trifle to me!”

The purchasers of freelance writing have a well-deserved reputation for responding as slowly as possible, thereby increasing your pleasure in much the same manner that the Pointer Sisters longed for a slow hand. I was pleasantly surprised in 2007 by the jackrabbit response of a publishing company to an over-the-transom Hail Mary I sent them. “Thank you for your submission,” their friendly, personalized form letter read. “You should hear back from us in approximately six months.” I set my snooze alarm for January of 2008, and waited for the big check to arrive, Ed McMahon-style, at my front door.

Time passed. Buildings rose and fell outside my office window. The Tampa Bay Rays went to the World Series, an African-American president was elected, the Arizona Cardinals played in the Super Bowl. We were surely in the end times predicted in the Book of Revelations, but I had to wait for a year after I received that first “Save the Date!” semi-rejection letter to get my official rejection letter. All I can say is, it’s a good thing I didn’t send them a live report from Pearl Harbor.

If one were to adopt this policy for a one-on-one transaction with a panhandler, instead of going through a middleman non-profit newspaper, the exchange might go something like this:

BUM: Hey man, spare a quarter?

YOU: Actually, I’d be happy to give you more than that.

BUM: You would?

YOU: Sure. Just send me a draft of a short, humorous piece about sleeping on heating grates.

BUM: That ain’t funny . . .

YOU: Well, no, not strictly speaking, but if you embellish it, and I take it, I’ll pay you within 30 days of acceptance.

BUM: (To another passer-by) Hey man, spare a quarter?

And then there are the unintended consequences of training the currently unemployed to become freelancers. My going rate for a +/-500-word article is $100; you will note there has been no price increase since I sold my first piece thirty-five years ago. My “hit” rate for print articles last year wasn’t bad, around 95%, which was Larry Bird’s career-high free throw shooting average, so I’m in good company there. On-line it was about the same, but the prices were a fraction—around 10%—of what print outlets pay. No wonder newspapers are going out of business.

So additional writing supply from panhandlers means prices will go down even further, leading to uncomfortable negotiations like this:

ME: . . . so that’s the news hook. Unless we rescind the Hungarian Toy Tariff right now we face the collapse of the domestic Play-Doh market, which will course through the economy like the chocolate part of Fudge Ripple ice cream.

EDITOR: Um-hmm. So . . . what kind of fee were you looking for?

ME: Well, my usual.

EDITOR: I don’t know. I met a guy sleeping in the vestibule who said he’d write a three-part series on how the Pope controls his bladder—for a 50 ounce jug of Thunderbird wine!

ME: (Pause) Okay, I’ll do it for a quart bottle of malt liquor.

Con Chapman did not get paid for this article. —Ed.

Con Chapman is the author of The Year of the Gerbil, a history of the 1978 Boston Red Sox-New York Yankees pennant race; two novels, Making Partner and CannaCorn; and over forty books of humor.

Jun 2, 2013

“Stag at Sharkey’s,” oil on canvas, by George Bellows, 1909.

by Robley Wilson

Once upon a time, my Uncle Laurence took me to see Roland Thibodeau fight. I was pretty young, but a boxing match in Scoggin was a rare event, and the appearance of the state heavyweight champion even rarer. Uncle Laurence told my father he thought it would be a shame if any nephew of his passed up the chance to see the champ, and maybe get his autograph to boot. Baseball and basketball games were all right as far as they went, he said, but they were sissy stuff compared to a he-man sport like boxing. Besides, he had a pair of ringside tickets.

Dad was reluctant. His opinion of men who hit each other was roughly the same as his opinion of men who owned guns: they were “ignorant and uncivilized.” In the end he gave in because, I think, he felt it would teach me a lesson to see grown men acting like animals. He didn’t consult my mother before he let me go. “It would only upset her,” Uncle Laurence told me.

I could see why. When we got to the Town Hall, we found the main auditorium had been mostly cleared of seats and a boxing ring set up in the center of it. Tarpaulin covered the floor, and around the ring a huge crowd of men milled about, talking and laughing, smoking cigarettes and cigars and grinding out the butts underfoot. The smoke was so thick, you could hardly see across the width of the hall. I started coughing when we came inside, but then I got used to the bad air, because I had to.

A fight was already in progress when we arrived, a “prelim,” Uncle informed me: two younger boxers just beginning their careers by fighting three-round matches leading up to the main event. It was pretty dull. We stood near the ring and watched a couple of men who looked as if they’d just got out of high school, chasing each other around the ring and sometimes landing a punch or two that didn’t seem to hurt either man. Then a bell rang, and they both sat on stools catty-corner from each other while other men in sweatshirts—“seconds,” Uncle Laurence called them—mopped the fighters’ faces. Then the bell rang, and the chase started all over again.

How old was I then? I was in sixth grade, which meant I was twelve. That was another part of my uncle’s argument: I was “old enough” for the fights.

I was certainly old enough for the prelims. At the end of three rounds, the two boxers touched gloves in the center of the ring, and the referee collected slips of paper from a number of men seated in folding chairs at ringside. Then he announced who had won the fight and lifted the winner’s hand in the air. Some of the spectators clapped, and some booed and whistled, but most of the crowd didn’t seem to be paying attention.

There was a second prelim, and then a third. The crowd of smokers went on milling, bells rang, men whistled or clapped. Uncle bought me a Coke from a concessionaire at the back of the hall, and treated himself to a cardboard cupful of beer.

“When do we see the champion?” I asked.

“Any minute now,” Uncle Laurence said. “Let’s find our seats.”

He had our tickets in his hand, and went off to talk with a big man in a brown suit and vest who seemed to be in charge of a double row of chairs set up around the ring. In a minute he was back.

“Pick any two seats,” Uncle said. He pointed to the front row. “How about those?”

We’d just got settled when there was a commotion at the front of the auditorium—applause, shouting, catcalls, and loud whistles like the kind you make with blades of grass.

“Here he is,” Uncle Laurence said.

Roland Thibodeau was about as tall as I was, but a lot broader, with curly black hair cut short, and bushy black eyebrows that met above his nose, which was wide and flattened out. A shiny black robe, red-trimmed, was draped over his shoulders; when he climbed into the ring, you could read the words “Flash Thibodeau” in thick red capitals—the word “Thibodeau” in smaller letters, so it would fit on the back of the robe. His seconds put a stool out for him, but he didn’t sit—just stood in the corner over the stool with his elbows resting on the top rope of the ring.

His opponent entered, with less commotion and less noise, about a half minute later. He was blond, taller than Thibodeau. His robe was purple, trimmed in yellow, and I wasn’t able to read his name until just before the fight started. He went to the corner opposite and sat down.

The crowd went quiet when a bald man in a tuxedo came to the center of the ring and announced the fighters’ names. Harland “Kid” Hartley was from Dover, New Hampshire, and weighed one hundred and ninety-eight pounds. Roland “Flash” Thibodeau was from Lewiston, Maine, and weighed two hundred and thirteen pounds. There were cheers for Thibodeau, a few boos and whistles for Hartley.

Then the two men met with the referee in the center of the ring. “Kid” Hartley’s face was younger than Thibodeau’s, and his robe wasn’t as shiny—the letters of his name a dull yellow script.

“Hartley’s got a glass jaw,” Uncle said to me. “You watch. Thibodeau’ll finish him fast.”

“What’s a glass jaw?” I wanted to know.

“It means if you hit him on the chin, he’ll go down like a tree.”

I looked at Hartley. He wasn’t much of a tree. Maybe Uncle Larry knew what he was talking about.

The meeting with the referee seemed serious. Gestures, a nodding of heads and, finally, the two boxers touching gloves and returning to their corners.

When their robes came off, the difference between the two was scary. Hartley was muscular but slender, with blond hair on his chest and under his arms. But Thibodeau looked like an animal, with black hair that seemed to cover his whole body—his chest, back, legs—the coat of an ape or a gorilla.

“Look at that,” I said. “He’s not even human.”

Uncle Laurence laughed. “But he knows how to punch,” he said.

And I guessed that was true. Thibodeau went at Hartley’s ribs so hard, you could hear the grunts, the exertion from both men. As the round went on, sweat looked the way it did in the funny papers—a spray of tiny droplets dancing off their bodies; you could almost imagine the word Whew! in little balloons over their heads. We were close enough to smell the fight, not only the sweat but the b.o., like something in between bad bathroom odors and a wet dog. As the first round ended and the second began, Thibodeau had raised his punches and was hitting Hartley in the face, bloodying his nose, opening a cut over his left eye. Hartley was coming back at Thibodeau, too, putting a bruise on the champion’s right cheek and making his left eye swell.

I didn’t know if I was enjoying the fight or not. Hartley seemed to be getting hurt; he’d slip inside Thibodeau’s reach and try to hang on—each time, they looked for a moment like two men dancing—but the referee wouldn’t allow it. He’d separate them, and Thibodeau would back away then throw another two or three jabs into Hartley’s face—until Hartley would try again to dance with him.

“He needs those clinches,” Uncle said, “or he’d fall down.”

Between rounds, Hartley’s seconds worked on him, replaced the adhesive plaster above his eye, washing the blood off his face.

By round four, every time Thibodeau hit Hartley, the blood would fly from his damaged nose and spray around the ring. In the third round, the champion forced Hartley against the ropes and pummeled him. The blood flew like a lawn sprinkler. It looked as if Hartley couldn’t lift his arms; you could see his knees sag. He was on the ropes right in front of us, and every time he was hit, he groaned like no animal I’d ever heard.

“The ref better stop this,” my uncle said, “or the champ’ll kill him.”

And the referee finally did manage to pull Thibodeau away and stop the fight. Hartley slid to his knees, then fell face down on the canvas. The referee raised Thibodeau’s right arm and said he was still heavyweight champion of the state of Maine. Most of the crowd cheered and whistled; a few booed. We all headed for the exits.

The fight had lasted almost four rounds and, as Uncle Laurence said, didn’t have much “finesse,” which he explained meant the difference between boxing and punching.

When he brought me home, Ma found out for the first time where he’d taken us. She was upset and angry.

“Look at you,” she said. “My Lord, you’re covered with blood from head to foot.”

And so I was, all spattered with it. From the look of me, you’d have thought I was the one who’d been fighting for the championship. Seeing myself in the bathroom mirror, my face and my white shirt dirty brown with the dried blood of the two fighters, was the best part of that whole evening.

Robley Wilson was editor of The North American Review for 31 years, during which the review won two National Magazine Awards for fiction. He is a prolific author of novels, stories, poems, and anthologies, including Dancing for Men, winner of the Drue Heinz Literature Prize, Kingdoms of the Ordinary, winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize, Terrible Kisses, a New York Times Notable Book, and A Pleasure Tree, winner of the Society of Midland Authors Poetry Prize. His most recent collection is Who Will Hear Your Secrets? published in 2012 by the Johns Hopkins University Press. He taught creative writing at the University of Northern Iowa from 1963 to 1996 and has been a visiting writer at Beloit College, the University of Iowa, Pitzer College, and the University of Central Florida.

May 23, 2013

“White II,” oil on canvas, by Mary Qian, 2011. Used with permission.

by Tony Hoagland

because

I like her. I like

the signs of wear on her;

the way her breasts have dropped a little with the years;

the weathered evidence of joy around her eyes.

I like her faded jeans,

her hennaed hair;

her hips pried open by the child.

I find her interesting; her grey-eyed

calm of a resigned sea;

her stillness like a painting on the wall.

It’s not that you don’t care,

but after all, you’re just a man

who has been standing in

water up to his neck for years,

and never managed to quite

dunk his head entirely under.

So give me your wife. Recycle her.

Look at her mouth, like a soft dry rose;

the way she stands, at an angle

to the world.

She could still be kissed and joked with,

teased into a bed

with cool white sheets;

convinced to lie and be

laid down upon.

Happiness might

still find a place

for her.

Give me your wife

like you were

unbuttoning something

accidentally

and leaving it behind.

Then just drift away

and let me try.

Tony Hoagland’s poems and essays have appeared widely. He is the author of several collections including Donkey Gospel, winner of the James Laughlin Award, and What Narcissism Means to Me, finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He teaches creative writing at the University of Houston and at Warren Wilson College.

May 22, 2013

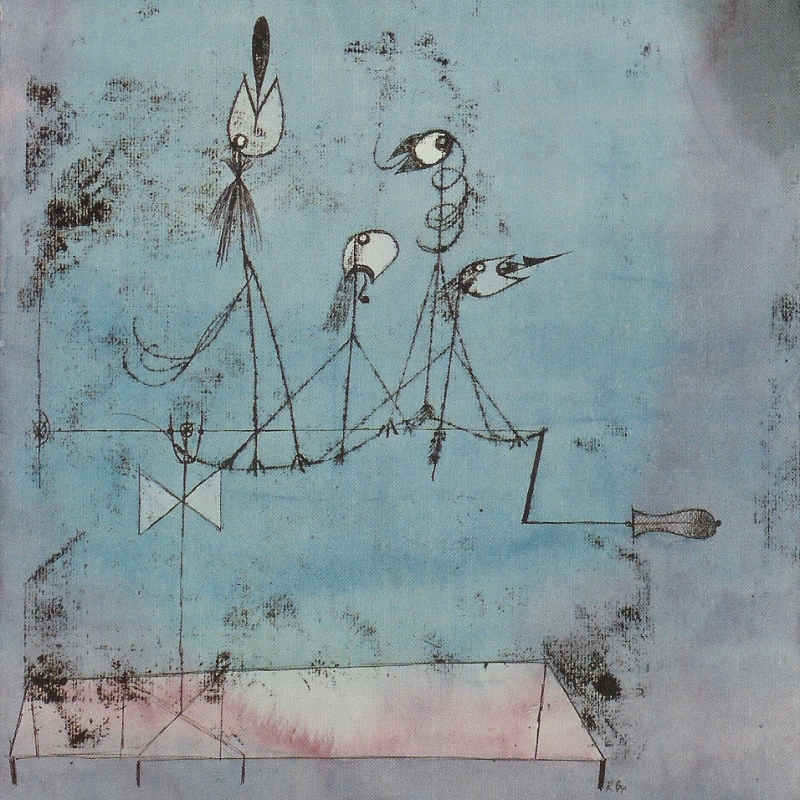

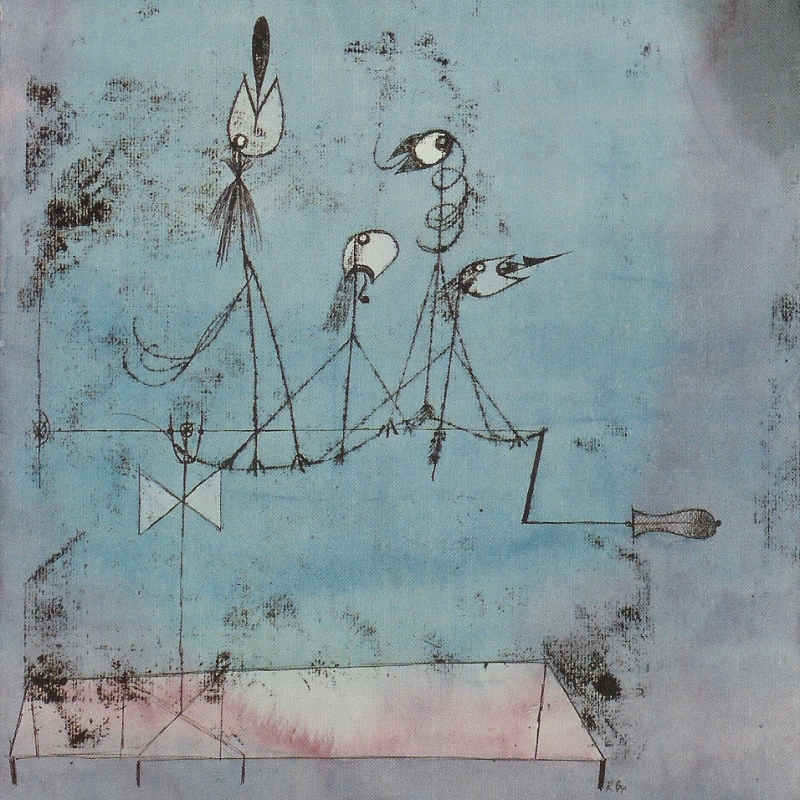

“Twittering Machine,” mixed media on paper, by Paul Klee, 1922.

by Karen Paul Holmes

Circumambulation: The act of walking around

something in a circle, especially for a ritual purpose

There she goes again, spinning

her wheelchair ’round the nursing home.

Two years, five thousand laps. So far.

With God’s help, she says, I’ll reach

eight thousand by this time next year.

Politely, the small town Sentinel

doesn’t give Bessie’s age nor why

she entered the home six years ago.

In her picture, a cannula helps her breathe,

yet she supplies her own determined air.

Neither wind, nor rain, nor oxygen tank

stops Bessie from what she calls her project—

I call it her prayer, her lifesaver.

More boomerang than arrow,

Bessie completes herself with each round.

Karen Paul Holmes’s poetry credits include Poetry East, Atlanta Review, Main Street Rag, Caesura, and The Sow’s Ear Poetry Review. Poems have also appeared in anthologies such as American Society: What Poets See (FutureCycle Press), and the Southern Poetry Anthology Vol 5: Georgia (Texas Review Press). In 2012, she received an Elizabeth George Foundation emerging writer grant for poetry.

May 21, 2013

by Lisa Cihlar

Does it matter that a migrating tern

is standing in the Fox River

with a goldfish in its beak?

The tern is a Caspian with a lovely black head

like the back-combed Italian mobsters in old movies.

The ones where the hit-men are usually two guys—

one skinny and smart-mouthed, one fat and dumb.

They are called The Muscle.

Sooner or later the mob-boss kills one or both of them

for failure to finish some job—

breaking thumbs, rubbing out rival mob-bosses.

If you take the Metra into Chicago

from the far west suburbs

you pass through a wooded area outside of Oak Park.

It is rumored that this is where the bodies are buried.

In the end, it matters to the goldfish.

Lisa J. Cihlar’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The South Dakota Review, Green Mountains Review, Crab Creek Review, Southern Humanities Review, and elsewhere. She is a two-time Pushcart nominee. Her chapbook The Insomniac’s House is available from Dancing Girl Press and a second chapbook, This is How She Fails, has been published by Crisis Chronicles Press. She lives in rural southern Wisconsin.