Jan 7, 2022

“Interior Strandgade 30,” oil on canvas, by Vilhelm Hammershoi, ca. 1905.

by Laurel Miram

The hand tremors hold off until the second “F” now.

“Progress!” the therapist says. “I know you don’t think you can…” But it’s not that. It’s not a question of strength. It’s about beginning. Or reprisal.

Pale yellow pads are best. They contrast well with black Sharpies. No one can miss a bumblebee. Bold shades feel childish, multi-colored stacks, desperate and chaotic. Pale is unpretentious. Professional. Informative, but not pushy.

“Do you think it matters to most people?” the therapist asks. Clearly she’s in possession of the answer. The question is essentially rhetorical. Most people don’t bother replying to that kind of inquiry.

A standard yellow Post-it pad contains one hundred adhesive sheets. Filling every page might sound gravely monotonous, considering the wording is identical, but adjustments here and there help. Spacing is limitless. Placement is indeterminate. And there are half a hundred ways to draw a line.

When its lettering is finished, each pad births a flip book. An illusion of moving words. Sometimes the words spawn pictures. They flutter to life—little, insignificant things, nonsensical but for shared proximity—and with the slip of a thumb or lift of a wrist, they are gone.

“I want you to try an exercise,” the therapist suggests. “Go to the grocery store and place your notes. Then go to another. Keep placing. Affix them until your hands are empty.” This is a thin trick. But, fine, there are worse ways to waste a day. Twelve stores, fifteen Post-its lighter. The lesson is unnecessary. It’s not about running out, using up. It’s salvage and courtesy. It’s warning.

“I want you to open the baby’s room,” the therapist says.

“I can’t.”

“Why?”

“Because I don’t want to.”

It takes five days to fill a 3×3 Post-it pad. More if life or people get in the way. Sitting on the floor is best, so long as the lap desk is available. Sometimes it’s put away—high in the linen closet—and climbing the stepladder stings too keenly.

“Let’s make a deal,” the therapist says. “Every time you feel the need to buy new Post-its, go on another search-and-stick spree instead. You can still soothe that urgency, that need to alert. Rather than stockpiling them, put those bundles to use. It will help you move forward.”

Emptying a pad is cathartic. But not soothing.

“That’s great!” the therapist cheers. “I’m so glad. I know it was hard to do.”

The baby’s room is next.

“How are you feeling about what we discussed a few weeks ago? I mentioned opening up the baby’s room—are you still against it?”

“I’ll always be against it.”

“You’ve made such progress with the Post-its. How many pads would you say you’ve filled, in all?”

“I don’t count them.” Why would anyone do that?

“Ballpark.”

“Seventy-five?”

“Could be a long time until you come to the end of them.”

There is no end to them.

“Maybe we should ramp up the timeline a little,” the therapist decides. “Let’s see where we are next week.”

How many grocery stores are within reasonable driving distance from any one person’s home? How likely is a shopper to unknowingly purchase food items that have dropped to the floor? How many people will heed the sharp drone of a pale caution and choose differently, giving thanks?

“So, how was the weekend?” asks the therapist.

“I visited thirty-seven stores.”

“And?”

“I flagged all of them. Especially the produce aisles.”

This is where most people lose their grip. Often they retrieve the fruits they’ve dropped. Some are wise enough to realize we cannot redeem every tender thing we let fall. If I see someone return a bruised product to the shelf, I knock it loose again. I tuck it against the racks and displays and cover it with a blacklisted Post-it—a little yellow jacket. Each thudded cantaloupe gets one. Fell on Floor, the paper jacket warns. Every rolling apple: FELL ON FLOOR. The tiniest tottering grapes—FelL oN FlooR. Dented soup cans, lurching chip bags, trampled cartons of sliced cheese. The crib. The playpen. The blanket with the fuzzy bees. And the door. Swarms and swarms of layers on the door.

“Paper Nests” originally appeared in Smokelong Quarterly.

Laurel Miram is a Detroit-born writer. Her work appears in SmokeLong Quarterly, OPEN: Journal of Arts & Letters, Eastern Iowa Review, and elsewhere. She is a senior editor for The Lascaux Review.

Dec 23, 2021

“Resting,” oil on canvas, by Victor Gabriel Gilbert, ca. 1890.

by Christina Litchfield

We meet on a Monday—I would never die on a weekend. You hate Mondays because the weekend means car accidents and those are often tricky and unpleasant. Tuesdays are much better, as Mondays are for suicide (who could blame them?) and those are much more straightforward. You push your briefcase or your purse into the locker and suit up for the day’s festivities. I’ve been waiting for some time but I’m not going anywhere. Pfft.

You were a child when you were interested in taking things apart, even if you couldn’t actually put them back together. You cut the worm in half and stared in shock, realizing that there was no way to mend the damage, no way to reverse the action you so recklessly took. You proclaimed to your parents in your senior year—I’m going to be a medical examiner. You mean a coroner? Maybe it was to prove that you could observe the mutilated worm without being the one who inflicted the pain. Maybe you became a coroner to avoid becoming a serial killer. I won’t judge.

You pull the drawer open and the tag swings. I have perfect toes that dug into the soft sand of the Pacific, the Atlantic and maybe back again. I often thought about what you’d think of me. My awareness of lying here stretched out for your inspection stilled my hands many times they reached for something fattening, high-calorie, headed straight for my thighs. I never wanted to disappoint. Your mother sometimes calls you a diagnostician when people ask what kind of doctor you are. Ouch. The crescent-shaped scar you’ll find on the back of my left heel got there when I was eight and breaking up a fight in the parking lot of my apartment building. The girl was bigger than me and her victim but I could reach her hair and drag her to the ground. I learned that fury at injustice can hide pain. You know that we build tolerance to most anesthetics.

My hands are soft and cold, dainty fingers that wanted to but didn’t play the piano. When you were in elementary school you took lessons; they weren’t as interesting as the worms. There’s a long scar on my right calf, like the serrated edge of a knife or the scalpel you hold; I have no clue how it got there but I always liked the mystery. Your hands are steady. When I was done having babies I went to Miami for a tummy tuck and—funny story—almost died. That long purple slash of a scar low on my belly is hard to miss. Kids and their aftermath are dangerous. You have a child someday but find that birth can’t outweigh death. It follows you to the break room and to your car and to your sister’s wedding where you say you’re a diagnostician when people ask what kind of doctor you are.

There is nothing else remarkable except for three tattoos that faded with sun and age. The Chinese characters on my right forearm—you take a picture with your phone so you can ask a friend to translate—mean “the fragrance of plum blossoms sharpens in the bitter cold.” I chose that one to ground me, so I could read it over and over late at night when I taught English to Chinese people and wanted nothing more than to run away. I didn’t run away. You like the black roses on my left shoulder, ones chosen just because they were beautiful. Sometimes beauty is enough. The swirling phoenix on my right shoulder blade appeared because it had been me or could have been me or I wanted it to be me. I want it to be me. You trace your fingers along the red ridge of a flickering wing. You get a tattoo just like it next year. You want it to be you.

Christina Litchfield is a second-year PhD Creative Writing student at Binghamton University and an online writing instructor at Arizona State University. Her creative nonfiction has appeared in Snapdragon: A Journal of Art & Healing.

Dec 14, 2021

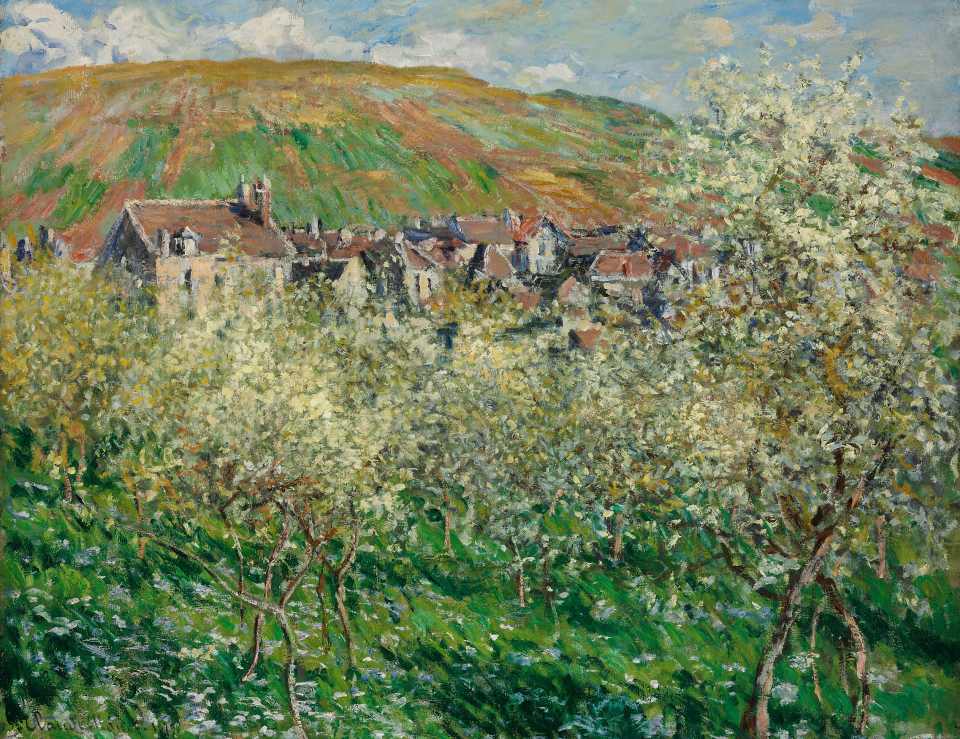

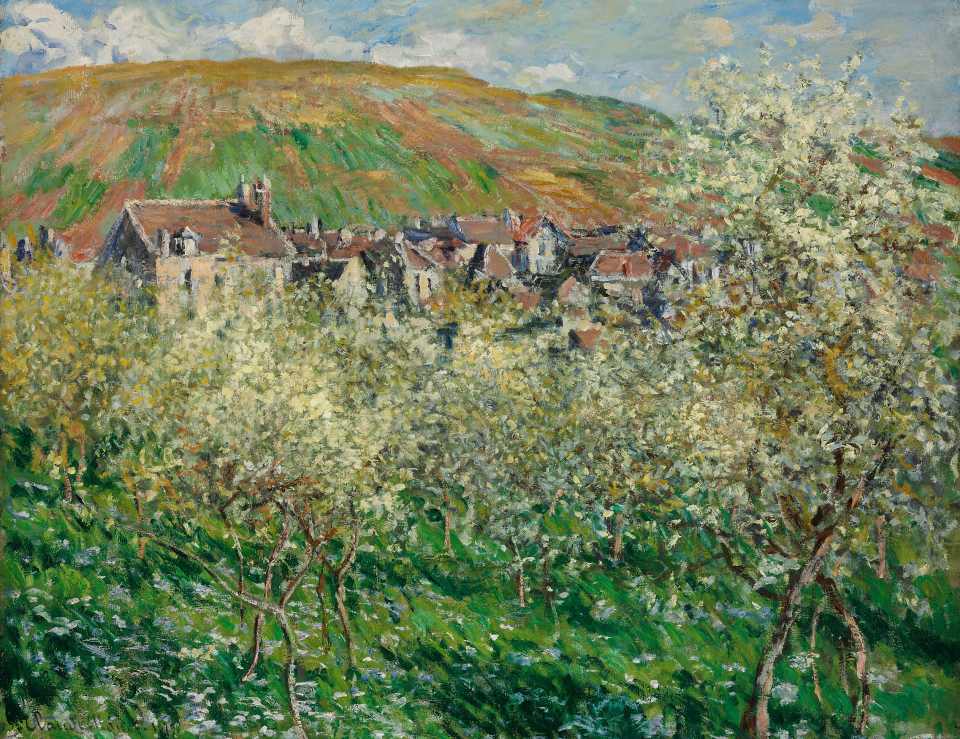

“Flowering Plum Trees,” oil on canvas, by Claude Monet, 1879.

by Mark Schimmoeller

The wild plums are blooming. They have bloomed every April since the man moved into the woods. The wild plums are blooming, a whole universe of them, and, God, every beginning of April, they block out the horrors of the world. The bees are there too, and he can’t hear the horrors of the world when the bees swarm the wild plums at the beginning of April.

The wild plums are blooming the year after epic fires across the globe. The man takes his chair outside to sit under a universe of wild plum blossoms and the humming of the bees until nothing remains but the blossoms and the bees.

The wild plums bloom the next year too, and the man is sitting in his chair under the blossoms and the humming of the bees, and now a sleek black pistol rests on his lap. The stain of a cardinal inside the white blossoms shocks the man, and the humming of the bees under the blossoming trees is a balm to his brain.

The wild plums are blooming, but it’s March. The world is off, yet the man is there under the blossoms, waiting for the bees, desperate for the humming of the bees. Come insects, come, everything has bloomed too early. The world is off, it fails us.

The man puts his hand on the sleek black pistol, and a zebra swallowtail lands on the barrel, so close to the man’s hand. It raises its black and white wings and lowers them, raises them, and lowers them, so slowly, like it’s the first time it has tried its wings, like it has just emerged from its chrysalis, and maybe anything then can be a stamen with nectar, even the barrel of a sleek black pistol, as the man sits under the blooming plums, until all that remains is the blooming of the plums.

Mark Schimmoeller is the author of Slowspoke: A Unicyclist’s Guide to America, a memoir that was shortlisted for the William Saroyan International Prize for Nonfiction. His short work has appeared in Orion Magazine, Mudfish, and elsewhere. He won the 2020 Mudfish Poetry Prize, judged by Erica Jong.

Dec 13, 2021

“The Wreck,” oil on canvas, by Knud Baade, ca. 1835.

by Tommy Dean

I might as well admit that I’m sinking. You know the joke about lifeguards drowning? Rip currents don’t care who they plunge to the bottom. Lake Michigan, a beast, roaring, devouring. Only in death, sanctifying. All sins washed away in the black print of your name in the paper.

The water thrashes around me; a movie I can’t pause. I’m separating from my body, each neuron a dry fire against the inevitable. Muscles ache and tingle as arm after arm goes out and into the delicate skein of the water.

I had laughed through the training videos. The mothers always so sad. Each one of them saying “He was a beautiful soul. A kid any mother would be happy to have. He was just starting to figure things out.” Then, on cue, they point to a row of trophies and certificates decorating the deceased’s room. They always zoom in on some goofy photo. A trip to Disneyland, a bike ride for diabetes, picking up trash on the highway.

Me? I’m a fuck-up extraordinaire. Swimming by myself, at night, half-high, the stars smeary like the headlights through a rain-soaked windshield. I’ll live forever or I won’t, the odds pointing toward something violent, painful, anything but boring. But alone?

Tired? Like a marathon runner stumbling through those last fifty feet, gravel scarring their knees as they crawl through the finish line. The water a swirl of limbs grasping, slicing through, tunneling me under each time my arm fails to complete the next stroke.

A message? Tell my mother not to use my senior picture, to find the one with my hair dyed blonde, my tongue out, hands air-jamming on an invisible guitar. Don’t let her find the ones where I’m drunk. Skin bruised, waxy like an apple left out in the sun, a riot trying to escape. Burn those. Let those be the ashes you scatter anywhere except over water. No more water; there’s nothing holy there. Back to the photos. Oh, that one from kindergarten, with the cowlick and the square teeth, the dimples. You could add a freckle or two. Make it look wholesome. She’d like that.

Tommy Dean is the author of two flash fiction chapbooks, Special Like the People on TV and Covenants. He lives in Indiana where he currently is the Editor at Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019 and 2020, Best Small Fictions 2019, Monkeybicycle, and Atticus Review. He has taught writing workshops for the Gotham Writers Workshop, the Barrelhouse Conversations and Connections conference, and The Lafayette Writer’s Workshop. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and @TommyDeanWriter.

Dec 12, 2021

“A Vanitas,” oil on canvas, by Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten, late 17th cent.

by Danielle Claro

Scavenged lectern, 2012

Wood, dirt, brass

This piece, rescued from the side alley of a brownstone on 117th street in New York City, was carried by hand on a commuter train 30 miles north to the village of Sleepy Knoll. It was then lugged a quarter mile on foot and delivered to the front porch of a woman who had once off-handedly expressed the desire for a standing desk. When the recipient arrived home from work the night of her 35th birthday, it is reported, she was frightened by the silhouette of the lectern, having mistaken it for an upright raccoon. Two weeks after the wobbly item was delivered, it was again among bags of trash. Some say it stands to this day in the garage of Sleepy Knoll’s Municipal Department, occasionally displaying a box of baked goods.

Inscribed compact disc, 1999

Polycarbonate plastic, indelible marker

Liz Phair was a U.S. singer of some repute in 1991, when the recipient of this Grand Gesture attended a concert, in San Francisco, California. At the time of receipt, some years later, the victim was pregnant with her second child, who herself would one day take the stage as a singer. The gift represents an apology by a husband for what appears to have been some sort of financial transgression. Papers do not reveal details, but experts believe the misstep to have been significant. The CD displays a pointed plea, in the celebrity’s hand. Scholars consider this work exceptional in the category, due to its alarming specificity and the collaboration of one who could reasonably be considered a “rock star.” This Grand Gesture was accepted with some degree of humiliation but was clearly valued, as it was preserved by the recipient in the sturdy Ziploc material common to the era.

Homemade “Don’t” flag, 2005

Acrylic spray paint on pima cotton

Though liberals in the mid-90s were adamantly pro-choice, there existed within this population a discernible discomfort regarding elective abortion for women in committed relationships. Many progressive middle-class marrieds who already had children, even those facing a high risk of divorce and/or severe financial insecurity (see previous work), were expected to soldier on with unplanned pregnancies, falling back on the refrain, “What’s one more?” This cloth flag highlights an urging from an unemployed husband to his wife of seven years, when she became unexpectedly pregnant soon after the birth of their second child. Financial struggles (recorded) made the wife’s choice understandable if not without pain. She headed to the doctor to terminate the pregnancy medically. It is unconfirmed but said that the husband chased the wife to the subway in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, descended to the far-facing platform and opened this bedsheet-flag the width of his outstretched, up-raised arms. The flag read, simply, “DON’T.” It is widely believed that the couple divorced three years later.

Carved sidewalk square, 1983

Concrete, water, forefinger

Lincoln Center, a cluster of midcentury buildings providing a home for the arts on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, was designed by iconic architect Eero Saarinen in the mid 1950s. It remains a hub of dance, classical music, theater, and film today, although recent events indicate a high probability of mixed-use zoning in the very near future. This concrete sidewalk square, poured in the summer of 1983, sat between Avery Fisher Hall (now David Geffen Hall, and originally Philharmonic Hall) and Columbus Avenue, which serves as eastern perimeter for the complex. Under cover of night, it was crudely carved with two sets of initials joined with a plus sign, in the traditional manner. The next day, it was revealed to the recipient, a dancer of adult age who, according to letters and diaries, walked on the opposite side of Columbus Avenue ever after.

Rough-hewn urn with ashes, 2017

Clay, glaze, human remains

Crafted in Taos by a ceramic artist who specializes in primitive renderings of desert animals, this coiled pot (plus contents) is arguably the most important work in the collection. It’s a fine study in humble presentation and long-lead commitment. The recipient—a woman in her late 40s, according to most estimates—lived alone. Scholars believe, based on strong evidence, that she had received two padded envelopes from a bereft former lover in the year prior. This item arrived in a small Amazon box two days before Christmas. Whether planned or coincidental, proximity to the holiday (plus the familiarity of the box’s logo) normalized the package, heightening its ultimate impact. “Unboxing” (to use the parlance of the time) was not witnessed. However, it is safe to assume that upon breaking the seal, the recipient would have seen a layer of silver tissue paper—another signifier of ordinary holiday goods. She would most likely have lifted the small covered pot out of the packaging. At this point, we must lean into conjecture. Either the recipient removed the coarsely fitted lid, peered inside, and saw a fair quantity of gray ash against the pale glazed interior of the vessel, or she found the note nested in the hollow of tissue paper left by the pot. The note was written in shaky felt-tip pen, most likely by a left-handed female:

“In my brother’s letter, he said this should go to you.”

Employing every classic device in the Grand Gesture toolkit—surprise, understatement, third-party participation, slow reveal—this work is a stellar model for students of the form. A major posthumous achievement.

Danielle Claro is a writer and editor. Her work has appeared in Real Simple, McSweeney’s, Domino, and many other magazines.