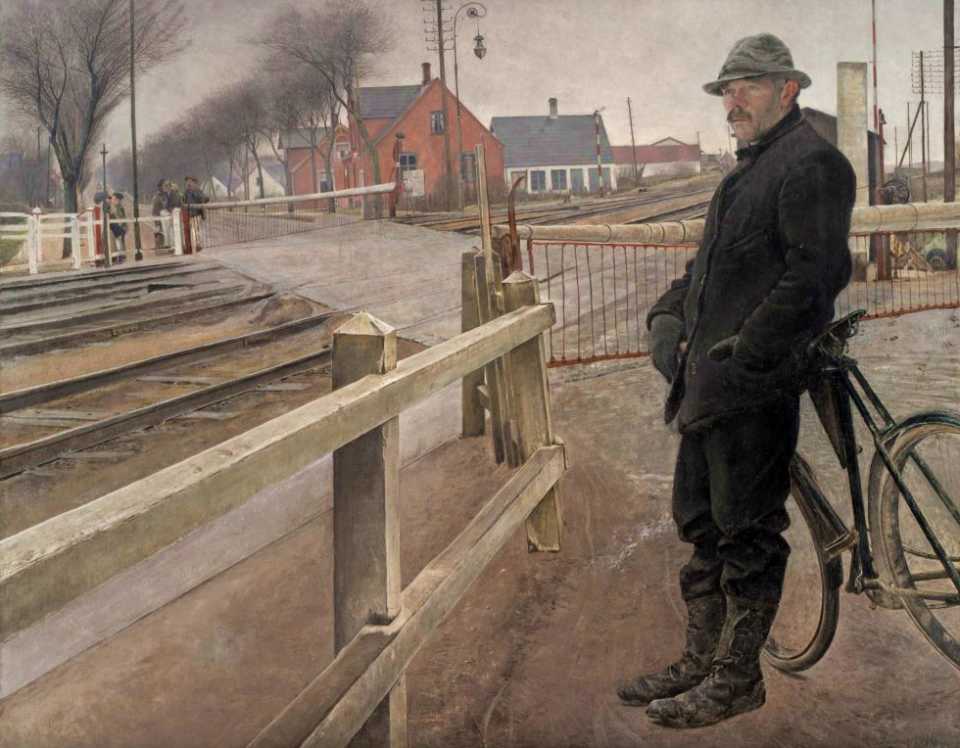

“Waiting For the Train,” oil on canvas, by Laurits Andersen Ring, 1914.

It was six-thirty when my father finished lubing Dreck Benson’s old Buick and took it off the rack. I pumped four dollars worth of high test for Butch Tobe and gave him a dollar in change. He mumbled but didn’t look at me. The wind from off the river tumbled trash and candy wrappers down the street.

Half a block down, Mrs. Henson turned on the IGA sign. In the bleak grayness of the early January evening, it was a yellow smudge. Dreck Benson paid and left. I turned off the kerosene heater over by the RC machine. My father turned off the gas pumps with a switch inside the door.

“Sleet in the air, Dooley?”

“Yes sir. I can smell it.”

We did not have to turn off the radio. My father told the mechanics, Ron and Pete, that it had a burned out tube. They just nodded. They knew better.

The old, green International pickup growled and spit, then started. We went out along Turner and then up Elm. Past the Texaco station where Denver Reese waved and Billy Cheatum lit a cigarette and pretended not to see us.

All the time I was thinking of those other days when Benny Jo rode with us. Talking about baseball or calling out to Francine Drell or Patty Majors, maybe wondering when he would get those straight pipes he wanted for that green over white Pontiac my father let him have. And even though it was five years ago, when I was eleven, if I closed my eyes, I could still see him there. His shock of unruly dark hair and that intense way of squinting ahead like he knew something wonderful and precious which he was not quite ready to tell everyone just yet.

At the Calvary Baptist, my father parked behind Reverend Cates’s station wagon and went to tell him that we would be missing the regular Wednesday night prayer meeting for the first time in twelve years, if you don’t count the spring flood eight years ago.

Thirty or forty of us scattered out there on those scarred, oak benches, facing the front and that big Baptist Creed. Quoting scripture and giving thanks. Strangers in a strange land, the Book says. Huddled together, beset by cares and trials unbidden, wrestling with our faith like Jacob with the angel.

But not us tonight, things being how they were.

Out on Miller’s Hill, we stood apart, him on one side of the grave and me on the other. Talking to ourselves, talking to her.

“I am sorry, Lucille,” my father said quietly. “The man with the salesman’s voice said they would do it at midnight down there at Eddyville.”

He stood there, shaking his head, his eyes closed.

“I got a ‘B’ on an Algebra quiz, Mama,” I told her. “Annie called last night. She said the baby was colicky. It’s going to sleet tonight. Maybe they will call off school.”

I twisted my red handkerchief in my hands. Four ducks lifted off a pond and flew south. I walked over and sat in the truck, watching the low dark clouds, racing each other across the lower sky like heavy smoke.

It was a hard thing to watch my father like this. He’d always had enough courage and certainty that it spilled over and he could give it away. Now he was lost on this high, cold plain of tragedy and doubt which he could not turn from or pray his way around.

I have seen him sitting in the counsel of fools, and when they had spoken whatever outlandish things their fevered brains could spawn, my father would nod as though he understood. Then, like some fantastical spider of magical design, he would take their ideas and weave them into a hundred separate threads of logic and something near truth. In the end, he would send them on their way, satisfied that they had spoken their piece and been heard clean and true.

But that was all gone now. This thing with Benny Jo had eaten at his soul like quick poison.

The wind whistled in the cracks of the windows. My father got in, rubbing his hands.

“Her grave is still sinking.”

“It’s that red clay,” I said.

We drove home without talking. I watched out the window to the wasted corn fields full of rotting yellow stalks. I thought of us, my father, Benny Jo and me, walking there in the crisp colors of September. Of Benny Jo flushing out a quail and yelling, “Get that lead bird, Dooley.”

At home, I put coal in the stove and went out to shovel some corn to the pigs. They squealed and fought in the mud, crowding out the runts. I pumped the trough full of water, knowing it would have a skin of ice by dusk. Back inside, I read the sports page and read my father a story about Stan Musial while he fried some bologna and eggs. We heard a car laboring up the lane, and I saw the sheriff’s car pull to stop by that puny maple sapling I had pulled up two year’s ago in Vanover’s woods.

Lehman Buford, a Pentecostal deacon and the county sheriff, stood over just inside the back door. His hands worked the brim of his hat.

“They are sending him home tomorrow night on the L&N, Darnell.”

My father nodded. “Me and Dooley will be there waiting in the pickup. I done got the burial permit through Maynard’s office. They going to let us bury him back in that old over-growed family plot back near that willow pond. Thanks for helping me walk through that red tape.”

“You’d done it for me,” Lehman told him with half a sigh.

“Sure you don’t want some coffee. Dooley made a fresh pot not more than half an hour ago.”

“Guess not. It gives me nerves. I’d be up watching them sing the National Anthem on Channel 7.”

Then he was out the door. A minute later, I heard his wheels spinning in that deep rut out by the mailbox, the one we keep meaning to dump a load of gravel in but just never get around to it.

After we ate, my father said that he was going out to check on the stock. I told him okay, that I would do the dishes, even though I knew he was just going to go out in the barn and climb up there in the loft. He would sit on a hay bale and watch across the fields toward the river. Thinking of his oldest son some where in a dim, gray cubicle, watching the clock until the warden and priest came for him. And knowing my father, I knew that he was wondering where he had gone wrong. Wondering what he could have said to intervene, thinking of all those times he was busy until midnight putting on new brakes shoes or working two jobs, the farm and the filling station.

I did my homework, Spanish and Algebra. The words and figures swarmed and blurred. After a while, I heard the mantel clock ticking loudly and the soft squeak of that rocking chair my Uncle Harley had made from green wood, where my father found himself a steady rhythm, pacing himself for the long evening. He would be looking at the picture of my mother, who had wasted away with cervical cancer, out of her head with pain and medication, telling my sister to get the cake out of the oven and telling Benny Jo not to kill that black snake. Singing in those last days over and over, that same plaintive Appalachian chant “…where is my wandering boy tonight? The boy of my tenderest care?”

We went to bed early. At ten forty, the phone rang. I scrambled down the stairs to answer it, my feet cold on the wooden floor. It was my sister Annie from up near Louisville, her voice soft and slurred. She was crying and talking, all of it mixed together.

“Don’t carry on so, Pig,” I called her by my father’s nickname for her.

“The man on the phone said we could have gone down to be there for him.”

“You know he wouldn’t want that. Daddy wouldn’t go anyway. Said it was morbid to go watch people kill your own blood.”

She was off the phone a second, and I heard ice cubes tinkle in a glass.

“It’s like I’m in a dream, Dooley. It’s like this can’t be happening to me.”

I held my tongue, resisting the impulse to tell her that it was not happening to her, that it was happening to Benny Jo, that it was happening to all of us. But we were both half muddled and dream-gaited. It didn’t matter. So I sat on the stairs and picked at a raveling on my pajamas.

“Maybe if he’d got that job on the barge or got that scholarship to Murray State and hadn’t busted his knee on that hay wagon. If damned Nettie Scales had not moved into town and wound him around her finger.”

I heard myself and thought it sounded like a petulant child, mad at the fates and whining over bad fortune as though that was something meant only for others.

“Nettie Scales was shot four times, Dooley. Billy Deems was shot twice in the heart,” my sister told me these things I knew already.

“Benny Jo wouldn’t hurt a fly,” I told her in weak counterpoint.

What I did not say while we held those silent phones across the miles was what I had thought to say to my father but then bitten back. That the Benny Jo who came back from Louisville for two Christmases was not the same Benny Jo who left us. It was as if the old Benny Jo had been eaten up whole and digested by this new creature who drank whiskey out of the trunk of his car late at night after my father went to bed. The kind of person who lived in a rat trap apartment in a bad part of the city and lay at night, grinding his teeth while his nightmares rode in full stride over the remnants of his dreams which were as thin and blue as vapor.

I listened to the sleet ticking off the roof, glazing the trees and roofs and roads.

Annie cried some more and hung up. I went back up to my room and lay there, trying to sleep. But it was near midnight now, and I was seeing the people come to his cell and lead him down that corridor. I got out of bed and turned on the lights. I had two old pictures of Benny Jo tucked in a yellow envelope in my night stand. I sat on the edge of the bed and looked at them. In one, he was maybe eight years old, wearing a straw hat and clenching his teeth around my grandfather’s corn cob pipe. In another, he was sitting on Uncle Eldon’s Harley, looking sideways at the camera and smiling that smile you would expect from a golden boy, who had always expected that earth’s bounty was descending to crown him alone for all his considerable worth.

When I closed my eyes, I could see him, coming out of the river at his baptism.

His face all holy and full of light as Brother Cates said the scriptures and raised him up from the waters of the Ohio there near Scuffletown. On the shore, we sang a ragged harmony, “Shall We Gather at the River.” When Benny Jo broke the water, he came up radiant, like he was a saint who had been in a cave a long time and had himself a vision of wild angels.

*

When my alarm went off at six, I crawled out of bed in a daze. I sat there on the side of the bed, watching the snow fly outside the window. What sleep I had gotten was spotty, slippery sleep, full of turbulence and sudden wakings. I did not have to be told that my father had spent the night in a lonely vigil, either in his room, flat on his back, or in the living room, rocking there in the darkness, swarmed upon by midnight doubts which flitter flutter like gnats which do not rest and will not go away.

I went into the dark bathroom and splashed my face with cold water, then down to start the coffee. My father was already out in the barn, milking the tan cow named Susie. The electricity had gone off during the night because the ice and sleet had snapped a power line or some hurry-scurry worker from the Alcoa plant locked his brakes on a tight curve and clipped off a power pole.

I heard the creaking of the back door and watched him coming in with the milking pail, a towel draped over it.

“No school today,” he told me as he poured the milk into the separator and put on the tin lid to keep out the occasional lazy winter fly which spawned in the walls and crawled out of that crack above the cook stove.

As we sat there at the table, stirring our coffee, thinking our separate thoughts which were only variations of the same thing, my father broke the silence.

“That your sister who called last night?”

“Yes, sir. It was her.”

“Was she making sense?”

It was a question fraught with his own knowledge of her nervous problems and her cure for them.

“As much as ever,” I told him dismissively.

He stood up and got out a roll of sausage.

“She’s just high strung. Maybe it would help if she married somebody who didn’t teach her that bourbon whiskey is a good way to set the stars straight.”

I nodded to him and scrambled some eggs in a bowl while he fried the sausage.

My mother would have fixed biscuits, but neither of us ever got past bad toast. We ate in silence and washed the dishes, putting them away carefully. It surprised our occasional visitor that two males living alone kept such a clean house. I think we just picked up what Mama had left us, some part of her kept alive in our rituals. It was a spare household, not a hint of real color except for the knick knacks she left us, some Depression glass and a See Rock City cream pitcher.

“You mind missing school and basketball practice?” my father asked as he wiped off the table.

“No. We got two teachers out on leave, and the coach is so busy trying to save his marriage, we mostly coach ourselves.”

We fumbled around a few more minutes, both of us in and out of the kitchen. Finally, he asked if I wanted to pray with him, and we got down on our knees. I listened to his words, tracing them over in my head like you can do if you grow up in a house and hear the same person pray over and over. Like a litany of sorrows and worries—the widows and orphans, the soldiers on foreign soil, those who have dwelt in our mercy and our love. Benny Jo just there around the corner of the words not said.

We got up from our knees, and the lights buzzed back on.

“I think I will go up in my room, son. My head hurts some.”

“Yessir. I’m going out to that squirrel tree near the new ground.”

I began to put on my coveralls and heavy boots. I got my .22 from the gun rack. I could hear my father’s steps upon the stairs, heavy and slow. I walked out the back door and across the horse lot and took a tractor trail along the ridge toward the river, a hard ball of ice in my stomach.

I went down to where Simpson’s Branch emptied into the Green River and sat on a rotting log and watched some barges go by, kicking up muddy waves which lapped against the bank. On a sycamore tree a few yards away, I could still make out where Benny Jo had carved a heart with the name of a girl whom he had loved and then forgot or she had forgotten him. Down the bank two hundred yards, near the ferry slip, Benny Jo jumped into the water and pulled me out on my eighth birthday where I had got caught in a strong current. He carried me to the bank, cursing and crying because he was the big brother who was in charge, and he was suppose to keep me out of harm’s way. He lay me in some muddy sand near a burned out campfire and pushed on my belly until I coughed up dark muddy water and then began to breathe. Then he went over and threw up in the horseweeds.

*

At seven-thirty that night, my father called up the stairs to say that Mr. Heppler at the train station had phoned. My father started the pickup, and we drove into town, sliding and creeping on the icy roads, both of us catching our breath and praying the truck out of those long slides where your stomach starts to turn. We parked the truck in that broken blacktop and went into the cavernous interior of the railroad station where the paint flaked off the walls and the exit signs had faded nearly out completely. The station had been built in the ‘40’s to handle the troop trains to Fort Breckenridge and Fort Campbell.

Three old men from down county were there, sitting around a pot bellied stove, spitting tobacco juice into the coal bucket and throwing us furtive looks.

We went out on the platform with the sheriff, and he got Posey, the porter, to get us a big loading dolly. In a few minutes, we could see the piercing beam from the front of the engine, and then it had chuffed to a stop. Three passengers disembarked, and then Posey led us to a baggage car where we wrestled the coffin down onto the dolly and then rolled it to the truck. As we slid the cheap, wooden coffin into the rusted bed, my father said, “Watch them sharp corners. You’ll lose a finger.”

I started to cry, but nobody mentioned it. My father shook hands with the sheriff, and he gave Posey two dollars.

Posey held up his hand and shook his head. “I won’t take money, Mr. Darnell. That boy was a ring tail wonder. I’d drag that box all the way to your house just for the strength of your son’s good, long laugh.”

“Okay, Posey,” my dad said. “Thank you.”

My father shook hands with the sheriff. “Thanks, Lehman. I appreciate your help. I know this falls outside of your official duties.”

Lehman Buford clapped him on the shoulder. “Darnell, you’re a Baptist, and I am a Pentecostal, and we have both seen the mouth of temptation. What I done was in recognition that could have easily been one of my own.”

“No matter what you heard, he was a good boy,” my father said, his voice suddenly gone weak and old.

The sheriff nodded and turned to go, but he turned back once more. “You done all you could do, Darnell. Five years from now, I will remember him hitting eight foul shots in a row in the district finals and beating Beaver Dam at the gun with that half court shot. I will remember him in the seventh grade when he got beat up by that Thurston bully for standing up for my daughter.”

We drove home with the radio on. “Your true lovin’ Daddy is movin’ on,” Hank Snow sang.

We parked the truck under the skeletal limbs of the slippery elm next to the smoke house. We had a certificate to bury him in the old family plot down by the pond where the snake doctors danced over the cattails in full summer. The church had a secret vote and asked that we not to bury Benny next to mama. Daddy said that it was all right. He’d figured it would happen, given what was on the radio and in the newspapers.

I went up to my room with a bologna sandwich and a glass of milk. I finished it and lay there on my bed with my clothes on, feeling a heavy fatigue welling up in my bones. I dozed and I dreamed of Benny Jo and Annie. In that sepia dream, I saw them bow to each other and then begin to dance. It was in our sideyard, over next to the apple trees. Snow began to fall about them, and they danced on, floating there among the snow flakes, like mythical creatures of great joy.

When I woke up, it was because I heard the car motor outside and then the door slam. I knew that it was Annie. Standing at the window, I saw my father come off the porch and go to take her in his arms, almost as though he had been sitting in the living room, waiting for those car lights to brighten the front window. Annie lurched a little, but Daddy caught her. I could hear her voice just a half note off hysteria. My father led her out to the pickup where he left her, leaning against the side, her head over on the cold wood of the coffin.

I should have gone to bed and given her privacy for mourning, but I did not. I stood there at the window, thinking of Benny Jo and Annie, growing up here in these upper rooms, their lives so pregnant with promise.

Then that other thought came, something so hard edged and true that it nearly took my breath away. What was my father thinking now? Was he watching me every day, not even fooled by what I said or pretended to be, always wondering when this last child would take some twisty turn and reveal that thing in himself which had gone sad and bitter at the core? Another monument to my father’s endless prayers and all those good intentions.

That was when I heard the noise in his room. A keening moan like some beast yoked to a burden which he had dragged like a rock too long but had gone on pulling it until this terrible moment, when he had seen the breadth and depth of his own hopelessness and despair.

I leaned my head against the window, willing the noise to cease. That was when I saw Annie as she began to struggle with the awkward weight of the coffin, pushing, shoving and hauling it until, by some unthinkable feat of strength, she leveraged it from the bed of the pickup. As I watched, half fearful and half fascinated, she dragged Benny Jo’s coffin inch by inch until it was beside the apple tree where I had dreamed the dance.

She disappeared from view for a few seconds, and when she reappeared, she was wearing what looked to be my brother’s old basketball letter jacket and the crown she had worn as the home coming queen.

She commenced like a crippled bird, leaping and jigging as her heels flung up tufts of dead grass and dirt, stumbling and falling, but always back up again. She shook her fists skyward, as though daring God to show his face and offer the least hint of his best defense.

Jim Gish was born and raised in Western Kentucky among the rogue Baptist tribes. He is a writer, a psychology instructor, and a counselor. His work has appeared in Phoebe, The Litchfield Review, and Alligator Juniper, and has won first prize in Fishfood Magazine’s national short story contest.