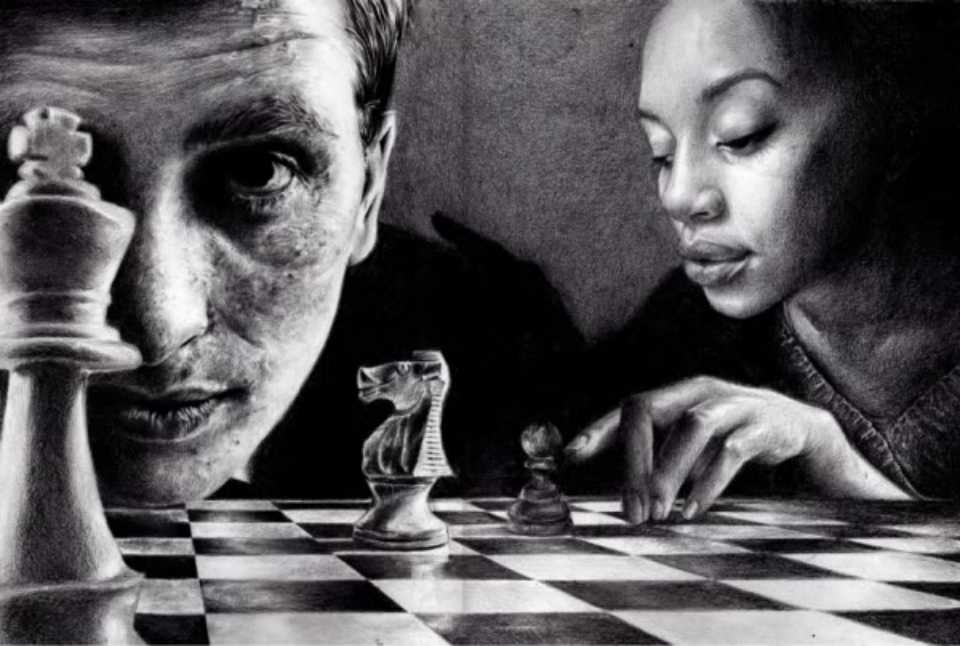

“Sabotage,” pencil on paper, by T.S. Abe, 2008. Used with permission.

A social researcher, she had actually been affiliated with Harvard University, part of the team which had issued an important, ignored report on the mental health of the American people. Normally, credentials didn’t faze me; but this was a credential that rocked. She was also nice to look at, and I was looking a lot.

A pretty middle-ager who knew she was pretty, she wore a white jacket over a button-down blouse and a pair of pressed jeans. Her jewelry was a series of subtle accents, rather than anchors, and her voice rose beautifully from the belly. She was the kind of woman other women would be quick to notice, but slow to condemn. She wore her sunglasses easily in her hair, tilted her head with an alert intelligence and had a habit of touching her hip, an unconscious gesture which heightened my attention and inflated my chest.

New to The Island and therefore probably shocked by the impossible cost of living and the impertinence of clerks and cashiers, she was a stranger to me, a name on some wooden crates in our warehouse where her stuff had been in storage for a month. I was one of three gentlemen making the local delivery, the one with the faded bandana on his head, a tiny diamond shining in his ear and a beard that was sprouting gray hair. I also had a case of God-begging loneliness. My life was a desert and women were water. So, yes, I definitely wanted to impress her. Maybe flash a credential of my own.

Briefly, I considered telling her that I was not only an artist in the field of furniture moving, but a writer who had once won a free ride through college on the basis of ten pages of poetry. Like all unpublished authors, though, I dreaded the inevitable question, Have you published a book yet? And so, smiling like a guy in a toothpaste commercial as I humped her belongings into her new home, I kept hoping the lady would catch a glimpse of my soul. Or at least notice my flexing biceps.

“And where would you like this piece, dear?” I asked, my voice light and easy as I struggled through her kitchen doorway with a bulky white leather chair.

“In the den,” she replied, throwing me a smile that damn-near tripped me, “facing the fireplace, please.”

Beauty, brains and manners, I thought as I set the chair on its legs in the den. Good communicator too. She didn’t talk down to me at all. And she was pouring out her guts from the get-go.

Originally from Texas, she had left her husband, an oil executive of the cowboy variety, after he (under the influence of vodka Martinis and lots of cocaine) had totaled the third Mercedes. This time, right on their front lawn when he’d missed the driveway and kissed a tree. Then he’d fallen into the foyer with a nineteen-year-old stripper, who’d announced, Hi, I’m Pepper, and I’m down for a threesome—got any strawberries?

“How did you know she was nineteen?” I asked.

“I asked her,” the researcher said.

“What were the strawberries for?”

“I have no idea; I left immediately.”

Adjusting the bandana on my head, I thought about strawberries and sex. How were they connected? What had I missed? Did I lack some new kind of creativity in the sack? Touching my diamond earring with a bit of worry, I went out to the truck for another carry, reciting inner affirmations all the way to keep pumping some helium into my self-esteem. It worked, and when I trudged back into the kitchen, hunching forward as I bore on my back a pair of cartons marked POTS & PANS, I was projecting fake confidence like a rock star, which the customer missed.

“After fourteen years of marriage,” she said, “my husband comes home with Pepper the bimbo then tells me to go get the Viagra. Can you believe it?”

I looked at her body without looking at it and got a little lost in her face. If this were my wife, I would not be crashing into trees with any fruity teenager. But yes, I could believe it. Alcohol has a way of manifesting the bizarre, cocaine accelerates what alcohol creates; and middle-aged husbands are notorious for the old-monkey/young monkey mid-life madness that always ends badly—or sadly—for everyone except the nineteen-year-old stripper.

“Terrible,” I said as I hauled the heavy cartons past her and set them on a stack near the stove.

Though I could appreciate the madness and misery of divorce, my sympathy for other people’s emotional injuries at the moment was not at high tide. My right shoulder was hurting like hell—it felt like ground-up glass in there—and those pots and pans just had to be cast iron. Furthermore, if I was not overly moved by her story, it was because I had heard it with minor variations on so many jobs before. People get freaky when they move and because movers are the quintessential nobodies, people tell their movers all kinds of private stuff. What’s your mover going to do—write a book?

“Is that all you have to say,” she asked, her tone as flat as the world before Columbus, “terrible?”

She was about to pour me a glass of lemonade. The pitcher was in one hand, a tall glass in the other. I licked my dry lips and reconsidered my answer.

“Pepper deserves the scarlet letter,” I said, “branded, not written, on her forehead. And your former husband should get both his boys snipped off. How’d you do in the divorce settlement?”

“Quite well, thank you.” She poured some lemonade and handed me the glass. “I used his own video as evidence.”

Liar. She knew what those strawberries were for.

I downed my lemonade, asked for another, guzzled that one as well and then thanked her with my hand on my heart. Though she didn’t know it, she had just passed her first test, seeing me as a person suffering from thirst and responding humanely. Her next test was whether she would remember the other two guys, who were so dehydrated their bodies had ceased perspiring. I sent her some gentle vibes to that effect but instead of picking up my psychic energy, she wiped an imaginary spill off the counter. Perhaps my brothers with their messier looks and lesser vocabularies passed under the radar of the lady’s social graces.

Okay, I thought, maybe next trip. She was way too pretty to judge harshly.

Then she told me her ex would have made an excellent case-study.

“He’s a perfect example of what’s wrong with us,” she said.

“Dysfunctional to the max,” I agreed.

I could see she was about to launch into it, the findings of her research. Like anybody whose work had been part of something truly significant, she wanted to yak about it, which was fine by me. I felt as if I could listen to that voice around the clock and it was refreshing to be communicating with an intelligent customer. But I also needed a cigarette, especially if we were going to get into anything heavy; so I asked her for two more glasses of her generous Paul Newman’s lemonade.

“For the other guys,” I explained.

She wasn’t going to get it without help.

“Where the heck are my manners?” she asked, pouring two more glasses.

Good save, I thought, giving her a B plus then told her I’d be back in a fast five. Waltzing the glasses like a make-believe waiter down the driveway and up the ramp and into the truck, I said, “Here, she thought you might be thirsty.”

“About time,” one said.

“What? No beer?” said the other.

Sitting on the edge of the truck, my legs dangling over the pavement, I went on the working-person’s vacation, resting my injuries and lighting up a butt. At first, I was only rotating my shoulder like a bird with a bad wing and begging the universe to let me win the lottery so I could hit a hospital and buy rotator cuff surgery. But pretty soon, I was actually on holiday, enjoying the breeze across my forearms and absorbing some of the sun on my face. Boy, reading those spiritual books was really paying off. I felt downright proud of myself for living in the moment and remembering to love whatever was in front of me. By my third or fourth drag, I was deeply seeing the flowering trees. Especially the pink one—a dogwood? Then I witnessed two white moths wiggling in the air over the lawn, and then a bumble bee. It was the big one, the queen, hovering like a B-2 bomber over some dipping daffodils.

Amazing, I thought, how suddenly every year it’s spring.

By then, vacation was over, so I stood up and sucked in my stomach again, combed the beard with my fingernails and bummed some chewing gum for the breath off one of my coworkers.

“I see how you’re working that nice-guy thing,” he said, tossing me a piece of sugarless. “That’s maybe gonna pay off for you. Chicks fall for that crap all the time.”

“You got a shot,” said my other coworker. “She’s definitely checking you out; so keep keeping your stomach sucked in. And cough up a sense of humor.”

“Hey, thanks for staying away,” I told them. “Very cool of you to give me some space with the lady.”

“Yeah,” said the one who was closer to the world, “so if we work together tomorrow, you can buy me breakfast, lunch and dinner. Just remember: Get her laughing now, you’ll have her moaning later.”

“That’s nice advice,” I replied, grabbing a pair of dining room chairs, “and if this were your typical Long Island chick on a barstool, I’d take it. But first off, she’s a transplant from a different state, not one of us. And second, she’s a woman of some depth and dimensions. Know what I’m saying, bro? She’s like a mansion with many rooms in it.”

He turned to the other guy immediately. “Bet you five bucks he blows it.”

“I don’t know,” said the other. “Some girls go for the sensitive type, especially if the last one was a monster. Plus, I think you’re forgetting the obvious: The pants of recently divorced women are famous for coming off fast. And she’s practically telling him her whole life story.”

“Watch,” said the worldly one as I stood there holding the chairs, “he’ll shoot for something all meaningful and drop the ball.”

“Maybe not,” said the one who seemed to be my supporter. “They’re both full of college and the overeducated ones get off on ideas. Didn’t you hear them when we were carrying the armoire in, talking about the failures of the American education system? That’s foreplay for them.”

“Then bet me.”

“I’ll bet you five he at least walks away with the phone number.”

“Like candy from a baby,” said the other.

“Hey,” I said loudly, “I’m still here.”

But neither seemed to care, so I split. Carrying the chairs up the driveway, I shook my head as if to escape a buzzing bug and just threw them both in the back of my mind with the beatings of childhood and a lifetime of rejections. True, when it came to seduction, I sucked. But this was different. I was not a book being judged by its cover. She was digging the content of my character. I spit my gum into the bushes and threw on a fresh smile, and when I stepped through the kitchen doorway again, my intellectual conversation with the babe resumed at once.

Actually, it was more like a lecture than a conversation. But I was cool with that. She was a social researcher and I was a mover. She was filling in my blanks. And the stuff she was saying was as real as it gets.

“Tell me more,” I said as I schlepped her possessions, and trip after trip, she did.

She spoke of our declining times as ominous, yet her tone remained matter-of-fact, almost scientific. I started to worry that she might be clinical in bed. But she also spoke as one having authority and because intelligence is almost as sexy as kindness, the blood-flow was affected quite a bit. Before I knew it, my mind was fast-forwarding to everything except our divorce.

She spoke; I listened. We were doing the Mars and Venus thing to perfection. And she was maintaining the eye-contact without a blink, so I was positive she was talking to me, the guy with the biceps and half a brain. God, it seemed, was throwing me a bone. I was just about to ask her what she liked to do for fun, but then the customer said something which arrested my attention like a choke-hold and crushed my lust like a phone call from Mom.

“The mental health of the American people,” she said, “is deteriorating rapidly.”

Rapidly—that was the word that got me.

She was seated on the kitchen counter, her denim legs crossed. I was carrying a white leather ottoman. I stopped moving. She had kicked open a door inside my head and across the floor of my consciousness a widening fin of light was spreading. I started thinking of things I had been thinking of for years, but seeing them differently, seeing them as mental illness, a collective insanity, a growing snowball rolling downhill.

“What’s the matter?” she asked.

I held up one finger to let her know I was thinking. Maybe she felt like a lady who had just been put on hold. That I couldn’t help. My mind was moving back through time—my own time—my personal period of American History and the view was quite a shock. I thought of all the streets I had known my whole life; what they had been like when I was a child and what they had become. I remembered how I knew my neighbor’s names and how now I knew only their fences. I remembered the kids I had gone to school with and how many of them were dead. Or in jails. Or in psychiatric facilities. Or so physically transformed by the psychological storms of their lives that they were nearly unrecognizable.

I’m no math-guy, but I even thought of statistics. Ten years earlier, for instance, The Island had five hundred gang members; now it had five thousand. And once, within my own life-span, it had been home to none. How was all this—and so much more—even possible in so quick a skip of time?

“You just nailed it,” I told her. “Deteriorating rapidly. That’s exactly what’s happening and it’s been happening for decades. What a moron I’ve been. For years, I’ve been listening to these people who keep saying we’ve always been crazy. But the truth is we are way crazier than we used to be. That’s a blatant fact. Which is probably why I missed it.”

Then I set the ottoman on the floor and sat down on it. Naturally, I presumed our discussion was more important than furniture, and that it certainly transcended our meaningless positions as customer and service-worker. After all, we were both in the same melting pot and pot itself was melting. And it sure felt good to sit down. I pulled the bandana off my head, wiped my face with it then stuffed it into my back pocket. She seemed surprised that I was bald, a bit of weirdness on her part which I chose to ignore.

“How bad is it?” I asked.

“Twenty per cent of the population,” she said without emotion, “if diagnosed, would be confirmed mentally ill.”

“Twenty per cent?”

“Yes.”

“And it’s getting worse all the time?”

Now she seemed impatient—fingernails clicking the counter. “Yes.”

My eyes were zigzagging back and forth across the floor tiles. My mind was a pinball machine of metaphors. Imagine one-fifth of an apple pie writhing with worms. Or a fifth of a book of matches on fire.

What happens to my country, I thought, happens to me.

I looked up at her with a stare that must have been a tad intense and I guess my face was pretty twisted. But we were talking about America, the emergency. And her opinion seemed critical. She was surely much more than some Paul Revere. This was a social scientist, affiliated with ivy, and one who had been out in the field. A mere messenger she was not. She had been collecting and assessing the evidence, and she probably had a whole saddlebag of ideas for solutions.

“What can we do about this?” I asked.

“About what?” she replied.

“About healing our nation.”

Her face soured; she appeared annoyed. It was almost as if she thought I was pretending to care about what she was saying in order to learn the color of her panties. Or did she think I was trying to shirk work? Or did she feel I was a flake because I’d used the word “healing?”

She was thinking badly of me, that I could see; but she was mistaken. Her lecture had awoken me. I wasn’t even looking at her breasts anymore. I wanted to hear more about our country now and what she thought we could do to help. And I wanted to do my part. Be a better citizen. More loving, more neighborly, whatever. Didn’t she understand that—and feel the same way?

Obviously not.

The transformation of her personality was as palpable as the zing of cold air on a cavity. She uncrossed her legs, slid off the counter. Under the shoulders of her light white jacket rose a shrug like a prize fighter’s. She touched her denim hip, but the gesture was no longer attractive.

“Whoa,” I said, “what just happened to us?”

“Nothing,” she told me.

She plucked the sunglasses from her hair, folded them slowly then slid them onto the counter behind her.

“Am I paying by the hour for this?”

I stood up immediately and picked up the ottoman.

“Yes, where would you like this?”

“That,” she said, taking a distant sip of lemonade, “looks like something that belongs in the den. Right in front of the chair it matches.” She tilted her head. “Don’t you think?”

My self-esteem was feeling like a sleigh ride straight down Suicide Hill. Deteriorating rapidly, I carried the ottoman into the den, set it down in front of the chair then kicked it in place. On the way back, I decided I’d ignore her as if she were some crazy homeless lady on the street. But the customer was two steps ahead of me, giving me her back as she washed my glass in the sink. She was so pretty, so ugly, and just like me she was now part of that twenty per cent.

Out on the driveway, I told myself I couldn’t make another carry. Not if I wanted to hold on to an ounce of dignity. I’d work on the truck for a while, lining the stuff up for the other guys, folding the pads and shoving back the feeling of being alone in America. I swiped a bead of sweat off my eyebrow and shook my head at a cobblestone. Where the hell was it?—the we of we, the people?

Don’t give a shit! I yelled inside myself. Just be like everybody else and get through the job.

I was coming up the ramp now and just about to tell my buddies that my shoulder was killing me and that I needed a spell from carrying, but my face must’ve said something else.

“Five bucks—pay up,” said one of my brothers, thrusting out his hand to other.

Raymond Philip Asaph is a Long Island furniture mover whose poems and stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry, Glimmer Train, Mississippi Review, and elsewhere. Write to him at longislandwriter at gmail dot com.