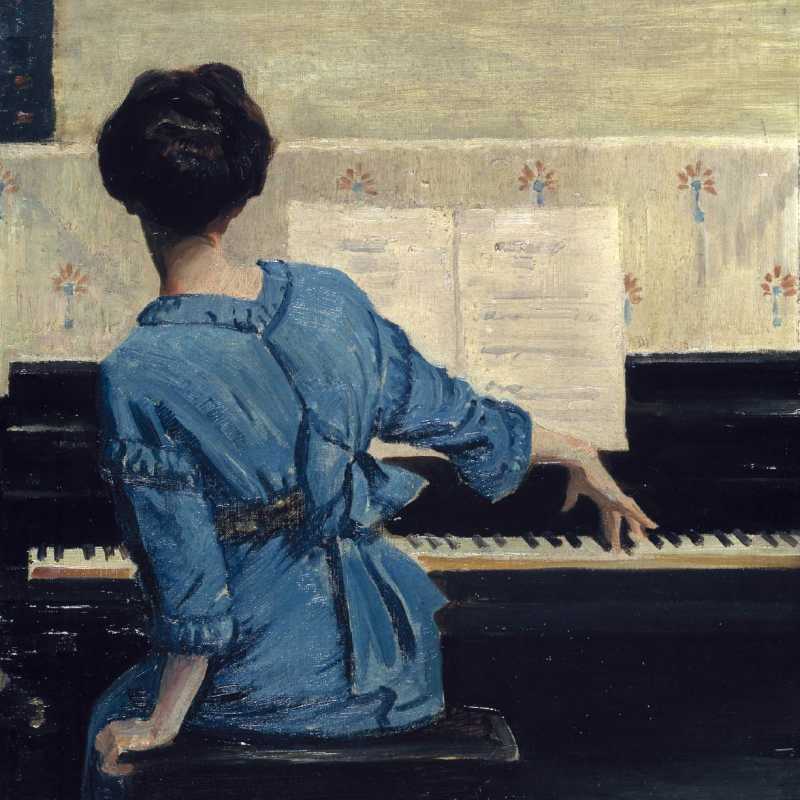

“The Keynote,” oil on canvas, by William Arthur Chase, 1915.

You wonder if you’ll see Christine tonight or if she’s still in California. You know nothing about California except that it grows oranges and you only know this because when your sister was little you had to fish one of those white produce stickers out of her mouth after your brother dared her to eat the rind along with the fruit. You try to picture Christine in an orange grove. Only you don’t know what an orange grove looks like so you have to make it up. Maybe it’s like the airport parking lot after a long trip. Every corner looks the same as the last. You walk and you walk and you walk and when you still can’t find your car, you give up. By this logic, Christine probably won’t be at your family’s Christmas party, but you dress up just in case.

Where are you going? Mama says.

You tell her, Out.

Don’t be late to the party.

You won’t be.

And pick up some ice.

Plenty of ice outside but none of it will do. It’s got too much road in it, too much car, too much bird-squirrel-possum-whatever-guts. Auntie TaTa likes her drinks to clink, not slosh. She keeps stepping over one dead husband to the next. Mama says, One day she’s going to trip.

What you like about Christine is the way she walks heavy and talks loud. She would make a terrible upstairs neighbor, but she’s the life of every party. And girls like Christine can always sing.

They say, No, really. I’m awful. But then, Maybe just one song.

The night you met her she asked if anybody knew Don’t Cry for Me Argentina on the piano. Suddenly the spotlight landed on you. All those years of sitting next to Mrs. Hernandez on the piano bench, waiting for the seat to snap in half. All those times her hairy arms skittered across the keys like little dogs. The neighborhood was full of dogs like Mrs. Hernandez’s arms, but none of them could play a waltz like her. You wanted to have that kind of power over the music, but you hated practicing.

Do it again, she’d say, again, again.

Your nightmares featured sheet music. But, look. Because of her, you were the one Christine wanted. The one she needed.

Tonight, you say a prayer for Mrs. Hernandez, who died last Easter. Patron saint of patience, over-indulger of Doritos. Crescendo, heart attack.

The best ice comes from the gas station.

Everybody knows this, Papa says.

You tell him you will be right back with the bags, but then you have to run your own errands. You’re 17. At 17 you’re allowed to have your own errands.

You forgot a present for Mama? Where do you think you’re gonna find something special now?

She likes Sprite and pork rinds, yeah?

He says that’s not funny, but hands you a ten-dollar bill and returns to his shoveling anyway. Winter has always been your favorite season, the quietest one. People drive less. Dogs hide under the bed and refuse to be walked. You’ve heard it’s because of the snow, that it takes up so much room, the sound just gives up, packs its suitcase, and goes somewhere else. That’s like Mama and Auntie TaTa at Christmas. Big, bossy ladies eleven months out of the year, but when the rest of the family comes to stay they get softer, softer, softer. So nice to see you, Mama says. Have another cookie, Auntie TaTa insists. Aunties and Uncles crowd the snowy street with their rust bucket cars. Someone knocks over the neighbor’s baby Jesus. All is calm. All is bright.

What’s shaking, Liberace? Was the first thing Christine said to you after Don’t Cry for Me Argentina. It happened in March. Winter was still holding onto spring like a child who refuses to leave her blanket at home, and as you walked across the parking lot with your sheet music, almost to the bus stop, her voice came out of nowhere. You turned around.

Hey, You said cautiously.

Shorts and a yellow sweatshirt, that’s all she had on.

I heard a rumor about you.

Old news.

Coming out in this town is like being the first person to jump into a lake, the one who tells everyone else if it’s too shallow. The sort of information you could only convey by drowning. You didn’t, though. Damn it, you swam. But it’s just like Auntie TaTa says: the water’s cold when you swim alone.

Christine held your gaze.

People spread rumors about me, too, you know.

No, they don’t.

Well, She said, they should.

Christine Brighton? Kissing you? You wouldn’t have believed it five minutes prior, but five days later you found yourself watching 16 Candles in her parent’s bed while they visited her grandmother in Santa Fe. The yellow sweatshirt should have told you Slow down. Proceed with caution. But it was already on the floor.

The Brightons owned a grand piano that nobody could play, so the moment her parents hefted their suitcases into the car for their next trip, Christine would sneak you in for a song. Forget romance. You couldn’t get a kiss until you’d given a Gershwin. Sometimes you played hints like All I Ask of You and she’d counter with a request for People Will Say We’re In Love, an exchange that basically meant keep your feelings down or the neighbors will hear. This went on for months. May, when Grandpa Brighton fell down the stairs and you spent the week kissing in every room of the house. July, when God blessed America and the fireworks drowned out your laughter. August, when you didn’t hear the garage door opening. The day she left you played Send in the Clowns on your family’s trusty upright, a song she would have hated, would have said, Too sad! Give me something cheerful.

*

You take the long way to Texaco to see if the lights are on at Christine’s house. If her parents are happier now. If they think the new school is working. It’s no secret you’re still in love with her. Your family understands that some girls want to be with other girls—Ay, sweetie, we get it! It’s all on TV—but what they don’t understand is everything you’ve done since she left. Where did our good girl go? Down the street, into the carpeted basements of miscreants, losers, and deadbeats. You picked up a foul mouth from your neighbor, Stanley. You returned it the first time you called Mama a bitch and got slapped so hard you forgot your middle name. Smoking didn’t stick either. Just the same old empty feeling, like reaching for change in the pocket of a coat and hitting the seam.

Come on, baby, just one song, Papa says.

But you haven’t played the piano since August.

The lights are on at Christine’s house. They even put up Santa.

What took you so long? Mama says as you kick the slush off your boots.

The kitchen is full of busy Aunties and clumsy Uncles. Mama tells you to make yourself useful, but the best you can do is answer the door when the first guest arrives, startling everyone with a shrill ding-dong and a Tupperware full of bourbon balls. Her coat forms the first layer on Mama and Papa’s bed. Later there will be dozens. A whole stratum of cheap wool and patchy rabbit that will remain un-excavated until well after midnight.

The room grows louder with every new arrival. Mama says, You shouldn’t have as people hand her bottles of wine and tins of butter cookies. She ushers the gifts to the kitchen to be opened and shared, all except for Mr. Romano’s salted toffee, which she tucks under the Christmas tree skirt. She will have it for breakfast tomorrow, a secret that everybody knows. As you sneak a bourbon ball from the snack table, someone taps you on the shoulder. Busted.

Merry Christmas, baby.

Auntie TaTa wears black for dead Uncle Alfie and shows plenty of cleavage for whoever will become your next uncle. She smells like gossip and eggnog, but you know she’d give you a kidney if you asked.

Your little girlfriend is here.

You remind her that Christine is not your girlfriend anymore. Not since her parents sent her away and she let them.

Isn’t this the season of forgiveness? Auntie TaTa asks.

I think you mean the season of giving.

So, give her forgiveness.

You wonder if she killed all those husbands like everybody says.

What happened to Uncle Alfie?

She tells you not everyone deserves to be forgiven.

A tipsy neighbor steers you towards the piano.

Jingle Bells! Silent night!

You beg off to the bathroom, say you’ll be right back. But, before you can make it there, lock the door, try smoking again to see if third time’s the charm, you collide with a familiar face. Fresh from the land of oranges, Christine looks prettier than ever. Her voice echoes louder than you remembered. Her shoes play drums with the hardwood floors. And when she says your name, you find it impossible to stay as mad at her as you promised yourself you would.

Can we go someplace alone? She asks.

No sense in playing hard to get; she is already holding your hand.

In this house, someplace alone is hard to find. You try the guest bedroom first, where a sullen Uncle Joseph exchanges his wine-splattered silk shirt for one of Papa’s sweat-stained hand me downs. The basement teams with sugar-spun cousins wielding Nerf guns. Up the stairs and in the pantry, Nana and Pop Pop spar.

Get out! They say. This is none of your business.

So, you pick a coat, any coat, from the pile on the bed and walk out the front door.

Nowhere to go but back to Texaco. North Star, open 24 hours. Christine’s coat, a fuzzy, brown duster property of Papa’s barber, trails the snow like a sleigh. Your short mink stops at the hip. Funny how she used to draw the curtains before you could even speak and now her hand is the only thing keeping you warm. Maybe things are different now.

What’s it like in California? You ask. Hot? Beachy?

Even the snow can’t swallow the huge sound of Christine’s laugh. She says California is more than just a postcard. More than just oranges, Hollywood. It’s a feeling.

How do I explain? She wonders.

I don’t know. I’ve never been.

You pump lukewarm coffee into Styrofoam cups. Ernie says it’s on the house.

Okay, how about this: in California everybody does exactly what they want.

Not like here?

No, not like here at all.

You always pictured Christine getting lost in the orange grove, searching desperately for a way out, but with her sun-soaked hair and hearty grin you’re finding it harder and harder to see her as a captive. She says she’s learned to surf. Tells you the names of her friends. Devin, Stef, Mackenzie, Dee. People so different from you they sound pretend. You should sip your coffee as fast as you can, knowing the cold air will render it undrinkable in a few moments, but you hold out. When the coffee is gone, you will have to turn around and walk home. Will she still be with you?

Devin says I’m a natural surfer.

Really?

Most people try for weeks, but me, I just knew how.

Last Christmas croons from the Texaco loudspeakers like a bad omen. Once bitten and twice shy. A frosted U-Haul full of people stops to use the bathroom, their legs wobbly from hours of travel, their children tottering forth in bright coats. You wonder where this family is going on Christmas Eve, if it’s much farther, if there’s room in the inn tonight.

Hey, says Christine.

As she leans close you catch the soft, tropical notes of her perfume. Not the cheap stuff she used to wear but something new, the type of gift you would give someone for Christmas. Someone you love. And, what? The girl who never kissed you in public all of a sudden finds the gas station private?

Wait.

What?

Before she can have you, you need to know. If people in California do exactly what they want, what exactly does she do in California?

Christine?

I have a boyfriend.

Isn’t California supposed to be safe? Teeming with glitter and megaphones? What about that famous mayor? As you rush to explain its merits, you realize you know more about California than you thought. You picture long, fake eyelashes on folks with beards, how happy those people must be.

So, what, you’re just starting over as someone else?

Wouldn’t you?

I’m actually pretty good with who I am.

Christine flirts with her shoes. And men, apparently.

But, I guess you’re not?

She tosses her coffee back towards the trashcan where it misses with a loud thunk, revealing just how little she drank. If you’re waiting for her to clean it up, dream on.

I want my life to be easy, She says.

You aren’t the one who’s hard.

*

By the time you make it home the coats on the bed have dwindled to a humble hill. Just the neighbors whose houses hug yours, the Aunties and Uncles who won’t go home until their children ask for Santa’s whereabouts, and Mr. Hernandez, who still can’t stand going to sleep alone. Mama lifts the snow-speckled mink off of you, shakes her head.

Welcome back, sticky fingers. Mrs. Holmes has been looking everywhere for this.

You tell her you’re sorry. She doesn’t believe a word of it until she gets a good look at your face. Then it’s: Do you want a sip of brandy? How about some of her special toffee? Only, don’t tell your brother and sister because if they find it they’ll eat the whole box and make themselves sick.

Love is tough, baby. Ask your Auntie.

Ask me what?

Auntie TaTa catches on as fast as Mama. She shepherds you gently towards the piano, where Silent Night has been waiting patiently all this time. Listen to the voice of Mrs. Hernandez in your head. Place your thumb on middle C. Then, wait until the shhhhh has made its way through the room, dampening the last few conversations and lit cigars. Until the loudest thing in the room is the Christmas tree.

That’s when you start to play.

Mary Liza graduated from Dartmouth College with a degree in English and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She also holds an MA from Dartmouth in Creative Writing and an MA from the University College Cork in British and American Literature. She is a Fulbright Scholar, a Virgo, and a proud aunt. Originally from Nashville, Mary Liza now calls New Orleans home.