“The Poor Poet,” oil on canvas, by Carl Spitzweg, 1839.

“How much for a love poem?” asks a young couple, clutching each other as if for dear life. Maybe they are. They’ve found me on Royal Street in the French Quarter, sitting at my Olivetti portable beneath the fortresses of balconies weeping with ivy. Doreen’s band is on the corner and she’s been holding a high-C on her clarinet for about five minutes and then Just, a closer walk, with thee, she pleads. I’m smoking Pall Malls, hungover—wearing an arctic-white three-piece suit with day-old mauve carnations stuffed into the breast pocket. The bell of a sousaphone presses its way above the crush of crowds, nothing but a brass halo disappearing around the corner like an evaporating angel. I’ve soaked up this identical exquisite moment thrice daily for years—now I can reckon time by its mimesis, by Doreen’s recycled setlist and solos.

“Pay me whatever you think it’s worth,” I tell the couple. “It’s a quasi-Marxist system: rich people give me one-hundred-dollar bills, and homeless people give me nothing but good karma, which I desperately need. It all works out in the end—most people pay ten or twenty.” They titter because they’re in love, and I’m fulfilling so many poetic stereotypes. His name is Matt and he has a wad of twenties thicker than my whole wallet. Her name is Cyndi and her vowels seem to have traded places. They met at a keg-stand six months ago, helpless to the electric innuendo sparking between their toned, happy bodies. Ribbed Solo-cups creaming over with foam. Celestial clockwork revolving furiously above them. Now, they’re getting married.

“Come back in ten minutes,” I say, rolling a slip of pink paper and swiping the carriage in time to Doreen’s drummer. Ding. They stroll down the flagstones of Pirate’s Alley, leaning on each other, either out of affection or from a few rounds of Hurricanes. I am weak, but thou art strong, insists Doreen, the words echoing through the French Quarter’s labyrinth.

I travel around the world and strangers pay me to write poems for them on a typewriter in the street—that’s how I’ve made my living for the last eight years. Often, I function as a Cyrano, a romantic-proxy, composing verses for blushing fiancées, or horny teenagers, or wives to send to their husbands in a prison/army/offshore oil rig. Or beautiful wrinkled couples, still wooing on their 50th anniversaries. I write gay sex poems—I imagine my body being pierced and combined with another man, even though I haven’t yet experienced that particular earthly pleasure.

The poems aren’t always romantic—strangers ask me to write about the rise of fascism, eco-collapse, dream-logic, suicidal ideation, lyrical necromancy. My typewriter becomes both confessor and inquisitor, tasked with humanizing and immortalizing in the same handful of minutes. One moment I’m hammering out an elegy for a still-born, and cataloguing a litany of psychedelic exploits the next. When it’s busy, I scribble a queue of bewildering topics on scraps of paper:

That I rely on the money from these poems to pay my bills heightens the whole equation. “What’s your day job?” customers often ask. The more cynical of them add, “Daddy’s credit card must be nice.” When I tell them I don’t have a day job, my parents are dead, and all they left me was alone—a confused, mystical expression crosses their face. As if Fate itself has led them here, to a sinking city on the vanishing coastline of a dying planet, to stumble across my typewriter. As if the maw of this obsolete machine could be a portal to an authentic dimension where love reigns supreme, somewhere that is sadly often in the recent past.

Sometimes my work borders on poetic prostitution, though I’m more harlequin than harlot. Only one block from Bourbon Street, where the real prostitutes ply their ancient trade, drunk white tourists armed with lime-green Hand Grenades demand me to immortalize their cat, who they’ve named after an African American hero, usually Satchmo. This crushes me. I feel tangible pain. Their poem might as well be a N’AWLINS! t-shirt featuring a voodoo-pirate-crawfish playing a saxophone. These are both the most difficult commissions, and the poems that earn the most money, the ones that make me feel like a clown-whore, the ones where I don’t sign my name.

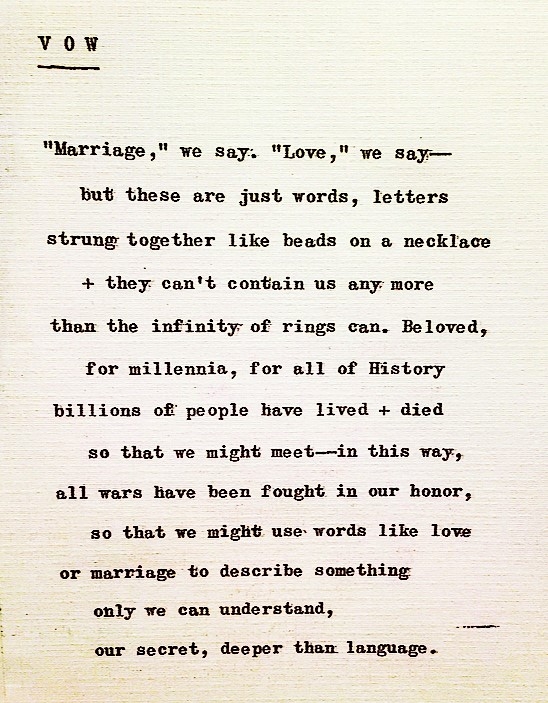

Matt and Cyndi, though, are sweet—but didn’t give me much to go on. They met at a party, they work vague office jobs. I’ve written hundreds of engagement poems, so it can be a real problem to tailor something original for a couple who don’t offer any fresh information. My hangover throbs. Not so long ago, I thought of myself as too pure for self-plagiarizing—or too proud. A brief tinge of guilt pulses through me for recycling imagery, as I type up a new version of a poem I wrote years ago, when my friend Levi got hitched:

Matt and Cyndi finish selfie-ing with the hapless St. Louis Cathedral, and scan the poem. Some sort of clear liquid leaks out the corners of Cyndi’s eyes. Matt infers that he will be extra-laid tonight and slips me a twenty. Our pageantry is complete. As they evaporate into the crowd, Doreen scolds me: Love, oh love, careless love. You go to my head, just like wine. I look up and the skywriter’s airplane has stitched a 🙂 face in wisps of cirrus above the cathedral spires—no wonder they wanted photos. I’m feeling so many emojis. Everyone is in love except me.

I think of these poems not just as a service and a vocation, but an act of redemption. Or exorcism. I’ve been in love in a minor-key, a few times—but only once when I gave all of myself. Her name was Isabelle, three holy syllables on my eighteen-year old lips. I was almost virginal in those days. Isabelle would lead me through her father’s pastures barefoot and we’d lie down in the grass and she’d instruct me wordlessly while her dog licked our feet—she was the daughter of dairy farmers in rural Vermont, where I grew up. She played the violin and owned a record player and her serene intellect intimidated me. Her bed was always full of impossibly-cool books, like Genet’s obscure plays in the original French, and smooth river-stones shaped like hearts that she’d leave between the sheets as we slept.

One night, in the half-light of her book-filled bed I studied the galaxy of freckles on her face and suddenly I knew. I love you, I said simply, but Isabelle didn’t breathe a word. She reached between her legs and produced a volume of Rumi’s mystic poems and calmly opened it to the page that read Gamble everything for love / if you’re a true human being, as if she’d been patiently waiting for me to be ready for this very moment. She had a way of reciting litanies with a single look, as if language itself were inferior, and not worth using to describe the things we did to each other.

I wrote my first real poems for her—about her furious mane of dark hair, and the storms that passed over her seraph-sailor’s eyes from time to time.

That was twelve years ago. Isabelle is married now, to a handsome man—from what I can divine from the crystal ball of social media—and works for some valiant health organization. When I say words like redemption and exorcism, that’s just a poetic way of confessing I was an apprentice cad, and cheated on her. Twice. And lied. In the bed of someone I barely knew, in a bed without river-stones or books I made my body an estuary where a selfish thrill and a sickening shame flowed into one another. Isabelle and I haven’t spoken in a decade—her forgiveness neither deserved nor forthcoming.

Since then, I’ve roamed around the world, writing other people’s love poems, never in the same place long enough to date anyone for more than a year or two. Paris, New York, Havana, London, San Francisco, Berlin—a litany of cities I use, rushing to fill up my cistern of memory as strangers empty it out again, poem by poem, stuffing their rumpled bouquets of currency in my hand. Ever since the grotesque aftermath of my mother’s death I’ve felt unmoored, cut loose from the real. As if I’ve entered a permanent déjà vu I won’t be hauled out of by anything other than falling in love again. Sometimes I think that by traveling, I’m searching for her—not Isabelle, but a woman as alchemical as her. Someone I would gamble everything for, to become the best-me, the person I was before I ruined and runed myself (though, once, in Marrakesh, in a penitent fever of hashish, I swore I could see her leaning out of a balcony window, her dark hair taut in the wind, searching for my face in the marketplace crowd).

In the City that Care Forgot, the sun’s yolk slips beneath the rooftops on Royal Street. All the clowns and statues have broken character, smoothing out wrinkled bills into stacks. Doreen packs up her clarinet and has no more prophetic advice to sing until tomorrow. A rare breeze gusts through the Quarter and my poems go flying—I have to sprint and lunge and stamp on them like cockroaches to get them back.

People trust me, a stranger, to write about love for them. What do I know about intimacy that permits me to do this? I’ve destroyed love callously—does that qualify me? I’ve mapped my grief over constellations no one else can see. I’ve flown thousands of miles in the belly of a metal bird. All those letters tattooed inside envelopes swollen thick as a hand—do they qualify me? Geographically, how many poems away from absolving myself can I be?

Strangers must read these questions, glyphs carved on my face in an alphabet I feverishly translate, city by city. Strangers must sense that I don’t know any more about love than they do, but I want it just as badly. Either to sing it, or mourn it. Or both, in the same molasses-slow moment, when we discover the reason we are alive. That love is what wheels us through a dying world that doesn’t make sense. That we all thrust ourselves into the fire, again and again, only to be brought out stronger each time, hardened and forged, hopeful. Out beyond our ideas of right and wrong, there is a field. Meet me there, said Rumi.

The typewriter is only a cage, where a creature paces, spooled and inked among the silk ribbons, waiting. Is there some key, a codex, a hidden combination of letters that will let it out? All I can do is pray to love’s wildness, to that moment in the half-light, when sound rushes through our throats and all language falls away, useless.

Benjamin Aleshire travels the world as a poet for hire, composing poems for strangers on a manual typewriter in the street. His work has appeared recently in The Times (UK), The Iowa Review, El Mundo, Boston Review, The London Magazine, and on television in the US, China, and Spain. An excerpt of his novel-in-progress, Poet For Hire, was runner-up for the 2019 Faulkner-Wisdom Prize and is forthcoming at Literary Hub. Ben serves as assistant poetry editor for Green Mountains Review. Find him at www.poetforhire.org.