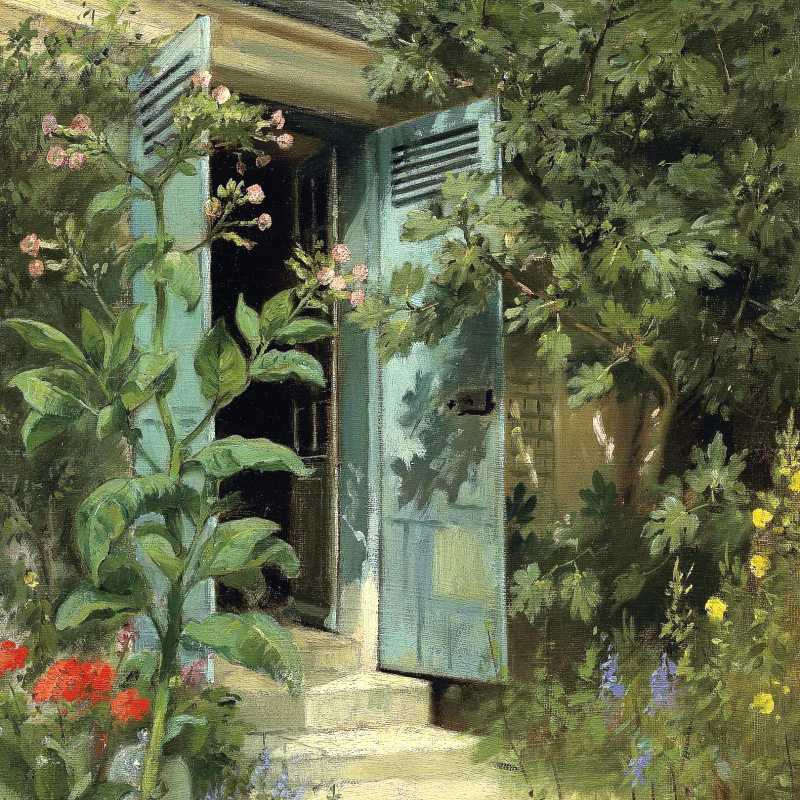

“The Steps by the Flowers,” oil on canvas, by Marie Adrien Lavieille, n.d.

It’s a traditional house, because every morning when the sun rises, when sweet yellow rays reach to kiss our bronze skin through the hand-sewn curtains and double-paneled windows, they only find mine. Habit. A syrupy morning dew floods my eyes, its own brand. Through the glass panes of the kitchen window I see my Grandmother and her shriveled pink lips that stretch and shrink and tell me the sun must always find the females first. Her buck teeth are barred, and her tongue spits house myths. I scrape cucumber seeds from their wet pockets over the marble island. And that’s only because Grandmother likes when I am at sacred work, upholding the rituals of a good Muslim girl. Habits and legends.

Her memory is one of my few possessions. I cherish it, though salt coats my throat.

Her reflection is still there, and then she tells me my brother, Matthew, will probably want an omelet and fruit for breakfast, and so I should begin. A ritual of old, heroic and such. I resist wrinkling my nose. Sticky pollen specks the silverware in the cabinet, and I laugh. Where are the bees? I’m loyal to my quiet cause.

I’m sick, sick, sick for it, though, wishing to neglect old tradition. An unwilling insurgent, but the modern woman is always under the weather. Is Father awake? Not yet.

This is a traditional house when I’m quiet and now that Mom’s gone, because whenever I wish to bury myself in text hugged by threadbare spines, poems of random sorts, scattered diagrams of brains, Grandmother asks me through our beige, patchy walls why I refuse to uphold the beautiful fables. When they’re so pretty, written dark in smeared navy calligraphy. Water stained now with disease. Her old tongue clicks against the roof of her mouth, and the sound pops through my ears. It stops me. Tangerine is stuck in my nails. Flakes of skin start to peel around the calluses of my fingers, always once winter arrives, and they remind me of dry cricket shells. I find them in corners under the stairs, all hallowed out like they were empty like that in the first place.

They’re wrong to be so dramatic. The drama grows when they stay there. They’re loyal to their own cause, too, my cause.

Tradition holds legend, and it’s golden because it is dying—skinning plums and the stench of wood polish. The more it dies, the further the gold thickens, and so housewife tales have become legendary. Grandmother spoke to Mom soon after she became golden, too, and so she used to read me myths like these at night. Grandmother’s raspy voice was, in the way nails against hoarse sandpaper might be, comforting. Familiar torment; it tumbles through the generations. I learned to hide my distraught under satin covers.

Adjust. A man will do what a man will do, and it’s your job to adjust.

Modesty is key to success, and so is the ability to shut your mouth.

Men don’t like loud women.

I learned to hide my distraught in hushed motives, and only the Tupperware and dust-ridden corners and satin sheets have a clue.

And I think that’s funny, because I live in America.

I frown as I suddenly notice the feel of fruit stuck in my teeth, the small orange slice I stole from my brother’s plate. I hope it’s citric acid doesn’t stain my taste buds.

Through the gaps in the covers I watched little red beads bloom from the corners of Mom’s painted lips when I was younger, already rouge enough; her tongue would flick them away quickly, but I caught those vermilion bulbs and found out she bit herself when she told me the legends.

When she was still at home, Grandmother too, I’d walk to the supermarket every Saturday morning, once celestial rays had sunken into me. Wind always fluttered around my headscarf, my hijab. Jellyfish around me would ripple in the wind. Cluttered shelves, bustling little women and their husbands and children, sharp mangled dialect all in true Arabic fashion, greeted me at the door. But when I saw the pistachio halawa stacked in packed containers on the fifth aisle and third shelf, I saw my reflection and Mom’s through the plastic. It is a favorite dish.

Each day I saw it, and it reminded me of her.

A savory-sweet image. Two strands of curly hair peek from under her hijab, her own cause, and she’s sitting on a thin white mattress on a cracked floor. My breath is warm when I exhale, lost in thought, and this spoils the chilly air. I pick at my chapped lips, bloody and torn.

Her eyes are lined with kohl, and they like to dart around her locked room. She asks for a piece of the halawa and calls me her love, ya habibi.

But then I find chunks missing. Chunks gone from the edge of her olive scalp and little bits of flesh eroded around her wrists. Slick black bars split her face in thirds. A pink line circles the base of her thumb. She wore her wedding ring there, a big silver stone that she lost in the wash. Pretty colors fill the missing parts, red, blue rivers in her arms, purple-brown swirls. Like hurricanes. It distorts her picture, until I realize she’s in a stone box with no bars at all, but instead a thin film of plastic barricades her away. Rainbows twist on the surface. The look in her eyes.

Her beauty is lost, as is her mind. I’ll never have the chance to confirm the vision.

I live in a traditional house of legends and gold with my brothers and Father. We live in America, the state of Washington. I have rights here, more than in Saudi, more than I’m used to, yet that star-spangled banner doesn’t kill Grandmother’s voice or mute it from the walls. Expectations and pressure of sorts.

The talk of legends. The will of a man against his wife and daughters, his power. The invisible whip of authority only Muslim girls see. And the men of this house don’t mind a maid. Matthew likes omelets and fruit in the morning. Aaron likes dessert.

The threat of stones choked Grandmother’s words, though. Throughout all her years.

But how are you, Mom? Do you like your baby blue gowns? Do the nurses feed you jello?

Egg shells crumble in my grip and the clumpy yolk spills onto my palms. I watch it spread for a minute. I live in the land of the free. The home of the brave. Grandmother whispers I’m free enough, more than she was, more than my mother, and I sometimes see Grandfather nodding his head, blotchy and bald in the corner with the old cedar rocking chair. Only on occasion. I’ve told my siblings they haunt me, but they laugh.

Crazy girl. And all that in the home of the brave.

Father once drove me, just me, in the family Toyota Tacoma to a lake somewhere far in the Olympic mountains, Lake Crescent. Mist and fog clouded my vision and quickly rendered our eyes useless, but the water itself was like a moving mirror. I peered over the edge of the dock, fenceless, and found clouds and the sky and chunks of myself missing. Gaps and gashes in my neck, my forehead. Rings of pink flesh circled my eyes and were connected by a thin line along the bridge of my nose.

I’m enlightened. Of course.

They looked like glasses. “Woke.” Father didn’t seem to notice, or maybe he didn’t care.

“This is where I met your mother,” Father sighed. His eyes, usually unwavering and unreadable, were seemingly sorry. He stroked the thick black hair on his chin and removed his thin spectacles. I sucked the inside of my cheek and tasted grapes. How strange to see a giant vulnerable and only tall in stance.

Grandmother laughed at me. A man is never sorry, silly girl.

This, when I live in America?

Mom chose to forget all that, Lake Crescent and my father, my brothers and her mother. How she did it, not sure, how did she do it? Tell me, Mother. Maybe the impossible caught up with her, the burden. I couldn’t forget, but could see the chunks out of her brain when I last saw her, right out of the top of her head. That’s where the memories were supposed to be. Perhaps my name was plucked out too. I wouldn’t know.

And so in substitution of surgery, I’m a patriot to my own loyal cause. Quiet defiance and such. The cricket shells will stay underneath the stairs, and pollen will cling to the Tupperware. I look at Matthew’s plate coated in swirling juices and pieces of shell.

I throw it into the sink.

I’m loyal to my own cause. Forgotten, far from legendary.

LaVie Saad is a junior who currently attends El Segundo High School. She has been recognized by Scholastic Art and Writing Awards and was recently shortlisted for the 2022 international Authors of Tomorrow writing competition hosted by the Wilbur and Niso Smith Foundation.