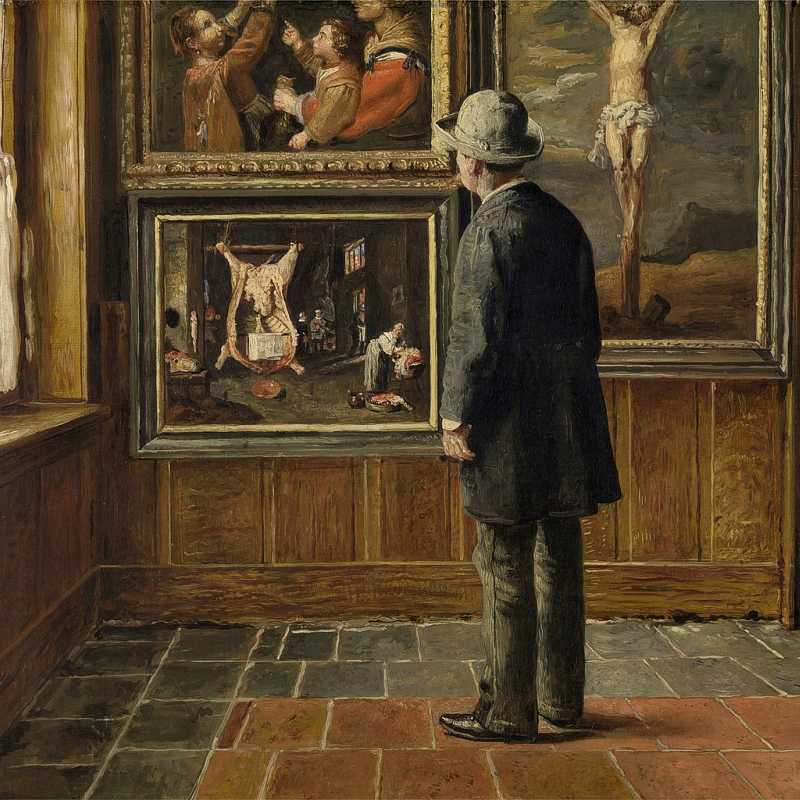

“The Art Lover,” oil on canvas, by Henri de Braekeleer, c. 1884.

In the museum of trauma, you stand back at least ten feet from each painting. Out of respect for other patrons mainly and the tacit rules of viewing. You don’t want the docent to sidle over in a loud whisper: Ma’am? Plus there’s always the chance of re-infection wedded to the benefit of distance—a wider lens that lends the full effect of an artist’s intention—each painstaking brushstroke melded into an overarching composition. The way say, at first glance, a Bruegel hamlet-scape renders a charming tableau of ordinary folk going about their quotidian; whereupon closer inspection, colored urgences burble to the surface: the same mundane individuals engaging in depraved acts of inane, if not insane, everyday cruelty.

In the museum of shattered dreams where you’ve attempted to grow from something raw, vestigial and two-dimensional an arboretum encased in two-way glass that lets you see out and no one but the sun in … the terrorist in your life slithers in through a sewage pipe—texts to apologize for thirty years of abuse and infidelity now that he’s found Christ. Asks you for forgiveness in a curt meaningless aside that may as well be a nail driven through your open palm.

Sunlight knifes the canvas between morning’s bare rim and roof of clouds. Your shared hostages older now, freed by time’s ransom. Safe in your new remove, you assumed you were done—obit written and shitshow shuttered at last—past praying to see him genuflecting in your rearview mirror. Now this—this nada footnote, one more scapegoat euphemized from the herd at random. Why now? and where to begin? the broken vow’s broken disc slipping as it skips over and over Thou Shalt Thou Shalt Thou Shalt … like anaphora like mantra like alphabet a victim never learns … abortions he scheduled unilaterally for your sons; the guns kept at arm’s length in case the vise of his manifold hands-on manipulations didn’t tighten tight enough; the time you were clutching your youngest on the ferry, he pushed you down the metal stairs with everyone watching and not one helped you to your feet.

How can a seed sprout without soil or sun? How can you begin to write a poem of your own atonement without specificity that might elicit him to own the slightest glimpse of your experience of him? If he can lift and take one, just one, from the litany hanging here and leave a blank wall for you to stare at to envision not a framed replacement but a ripening bright fresco, the wall itself espaliered, transfigured in freedom … How can a destiny reboot or reckoning take root without a rendering? How surrender to an alphabet that can’t articulate a single particular, that can only muster in a follow-up text: You don’t have to forgive me, it’s up to you. Up to you—like everything else: from hills of bills you climbed, to boys you raised to men, to peace you prayed for, if only in yourself.

You step back and take it all in. The artist, her composition. The gallery empty, except for a small unaccompanied child who enters the frame of your vision, beelines for the painting, his hand outstretched, pointing to a figure he’s sure is him, touching where soft bristles left their hardened mark. You wait for a docent that never comes to tell him what no one will, to remind him what sort of museum this really is.

Author of the Grolier Poetry Prize-winning collection Some Far Country, Partridge Boswell is co-founder of Bookstock Literary Festival and teaches at Vallum Society for Education in Arts & Letters in Montreal. He lives with his family in Vermont and troubadours widely with the poetry/music group Los Lorcas, whose debut release “Last Night in America” is available on Thunder Ridge Records. His Saguaro Poetry Prize-winning chapbook Not Yet a Jedi is also now a thing.