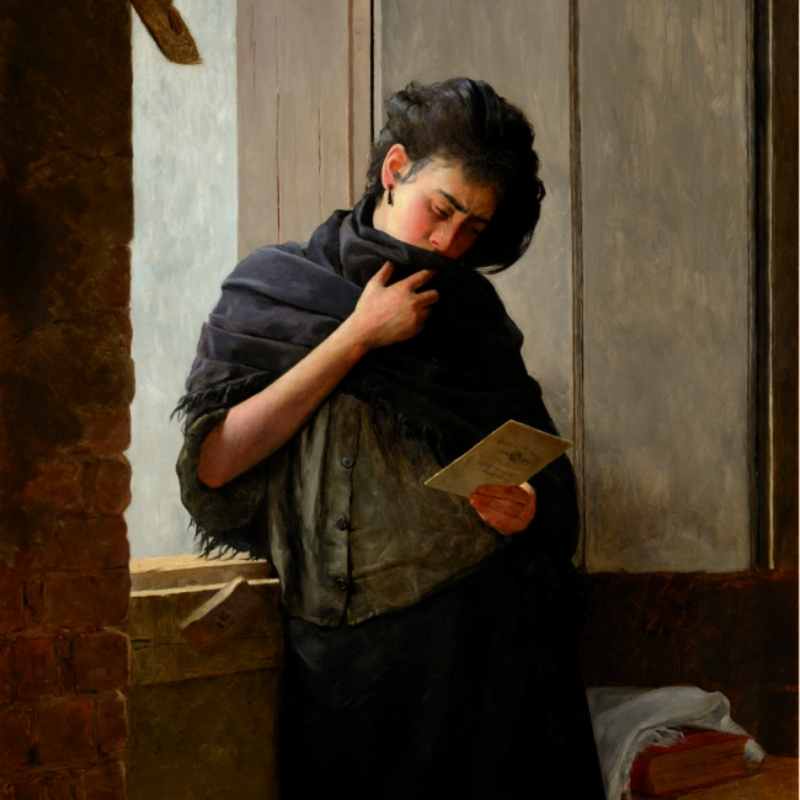

“Saudade,” oil on canvas, by José Ferraz de Almeida Júnior, 1899.

Now that Kate was safely out of the way—silenced permanently in a corner plot with a view of the freeway—the pedigreed vultures swooped in. These scavengers of the literary community who had circled throughout her illness wanted her papers: rough drafts, outlines, sketches, and character studies, but mostly her letters. She left hundreds of letters behind written in her quirky, tight hand, in her personal style, with her enchanting sense of humor. I had gotten my share of them over the years, so I knew exactly the object of their dried-up, academic love.

Despite the persistent wooing of her publisher, her alma mater, and one Professor Graham, who harbored an unhealthy professional infatuation, I avoided Kate’s office during my slow progression of prying her things from our house. Admittedly, my delay in dismantling this last bastion of her was only partly to frustrate the academics. Mostly I knew that handling paper she had touched, that had touched her, was going to be exponentially harder than emptying her underwear drawer and confronting that half-eaten box of Wheaties just out of my short reach in the pantry.

To me, reading was heroin, a drug I mainlined at every opportunity and that transported me as surely as that poppy derivative. I read not only at normal times—in the tub, before bed, on my commute—but also while I brushed my teeth or scrambled eggs or walked to the grocery. Librarians knew me by name, and I’d once had to move to a bigger place to accommodate all my books. The most compelling proof of the existence of God is that I shacked up with a writer, and truthfully, my love for Kate just barely trumped my love for her words.

All of the thousands she’d left behind in her office tempted and scared me in equal measure. For months after the funeral, I was unable to cross the boundary of that long-closed door. Every time I eased down the hall past this tomb, I couldn’t shake the image of Kate, sitting cross-legged in front of the bank of black file cabinets just inside, reorganizing for the umpteenth time, laying down playful posthumous commandments about the folders strewn about her.

“Don’t let anyone in here, Audrey. If you have to, box it up and deliver it. Claim you were the one who put everything in order. Whatever. Better yet, just torch it.”

All I could do was laugh. If I’d said anything, it was always something like, “Who are you kidding? You’ll outlive us all.”

But she didn’t, and now I had to consider how much of what she said was real and how much was just the conflict between her inner compulsive and her public, bless-this-mess persona. She’d had years of illness during which to decide to bequeath them or destroy them, and she hadn’t done either, so eventually, I had to choose for her. Kate’s publisher forwarded proposals to me, and I sifted through them until one morning, I opened my front door to Walter Rosenberg, a no-name adjunct professor at a no-name college two hours away. I’d chosen him mostly because of the large upper hand it afforded me but also because of something he’d written in his dissertation on the modern Midwestern sensibility in literature: “Kate Harrison is subversive in how she approaches heavy topics like race and socio-economics, laying them right at the surface of her prose without once interrupting the story underneath. Such a tactic is not the typical Midwestern one yet is extremely effective. To read one of Ms. Harrison’s novels is to come out the other side exhilarated, amused, and forever altered.” Forever altered. Yes.

Walter was impossibly young with an unkempt puff of light-brown, curly hair and a prominent Adam’s apple.

“Walter,” I said and shook his hand.

“Ms. Bishop. Thank you again for this opportunity.” His eyes flicked past me to the foyer and beyond then back to my face, but I couldn’t quite get myself to let him inside.

“I have rules.”

He blinked, glanced up and down the block. “Okay…”

“First, no papers leave this house. Second, I retain the right to withhold anything we find. They were Kate’s words, and now they’re mine and everything that implies.”

“Absolutely. I get it. I read through that agreement the lawyer put together. And Ms. Bishop, let me say—”

I held up my hand. “This is not about you or me but Kate. I believe in the power of her words. All of them. So here we are, whether you need it or not, though I know you do, or whether you deserve it or not, which only time will tell.”

Walter’s serious earnestness slipped, revealing a grin that somehow made him look older. “Why do I feel like I’m trying to take your daughter out on a date?”

That was so much like something Kate would say that I came shockingly close to laughing. “All right. Come on.”

I led him through the foyer and living room then down the hall, and when my hand landed on the knob of Kate’s office door, I made myself turn it without hesitation. The cool air inside smelled like Kate before she got sick and turned sour like milk a day too old. At that scent and the sight of those filing cabinets, I knew this was still too soon. Then again, most mornings I still woke up thinking Kate was lying next to me.

Walter cleared his throat. “I meant to start out with my condolences for your loss. She was … I saw her at a reading a few years ago, when I was finishing my dissertation. The way she told a story—and not just on paper but with her voice—she was a performer. She seemed like your cousin Ruth or something, the one your parents loved but told you to keep away from the wine.”

“It was an act. At least partly. She was probably already sick then.”

“I’m sorry.”

I inhaled sharply. “The drawers and files are all labeled. Most people wanted to see her letters, but you were admirably vague in your proposal.”

“That may be the first time those words have been used together in a complimentary way.”

I wondered, briefly, why he didn’t have a tenure-track position yet if he were this clever, but I just said, “Where would you like to start?”

“Um … top left?”

The ice inside me melted a little at that. I opened the first drawer and tugged out a thick folder of yellow paper, which turned out to be a hand-written novel Kate had penned in college. We read it tag team with my passing each chapter to Walter after finishing it. The prose was so wonderfully awful compared to what I was used to from Kate that I laughed for the first time in a geologic age, imagining her writing it.

This exercise was going to take weeks. Months. And if this train wreck of a novel were any indication, I was going to fall in love with Kate all over again with each story. Even her bad writing brought her back to life in the same way she was conjured into existence whenever anyone opened a book she’d written. She hovered over your shoulder and spoke her words into your ear with her flat Midwestern accent, slapping you on the back over every good joke.

I remembered too well how Kate was at readings, especially the one at my local bookstore where we’d met. There she was on a random Tuesday after work, larger than life, so bright and bold and maybe a little too electrically there to be my type, but when she started to read, oh, I was mesmerized—not even by her words but by her vowels and consonants, even by the pauses between them.

When she finished reading, I picked a copy of her book off a tall stack and became the end of a line of people waiting for her signature. No one appeared after me, so we were alone when I arrived at her signing table. As a child, I’d had crushes on writers rather than rock stars, and I handed her the book with no small amount of trepidation, praying to God that her words would live up to her.

Her eyes were a warm brown and made her more approachable than her blunt-cut, chin-length hair and raucous laugh. A light spray of freckles decorated her cheeks, and I flushed so fiercely I all but shook with it. “That was a wonderful reading.”

Kate’s smile widened enough to dimple. “Thank you. I changed my mind about what to read at the last minute, so I wasn’t sure how it’d go over. Do you know how many of my writer friends spend the remaining seconds before these things with their red pens out, editing right on the printed book? We’re a mad bunch, I guess. Shouldn’t be let out in public.”

Yes, reading was my chosen drug, but Kate Harrison was the drug distilled and personified, and before I knew what I was doing, I’d offered my hand and introduced myself.

“Audrey,” she repeated, took my book, and turned it over in her delicate fingers. “Do you drink coffee? Tea? Bourbon? I’m dying of thirst, and as wonderful as the staff is here, what do you say to sneaking out with me?”

Whenever the plot of my life twisted and bunched, I floundered around in stupefied indecision, and Kate must’ve mistaken this for serious hesitation. She looked embarrassed, her thin brows wrinkled. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have. Here, let me sign this. I wasn’t trying to hold it hostage or anything, I swear.”

I found solid ground at her fluster and reached for the book. “Forget the signature, and let’s get that drink.”

Walter came over weekends and evenings—whenever I would let him and was around to supervise, though supervise probably wasn’t the right word. Mostly, I didn’t want to miss anything. Sometimes, while I pored over story drafts and character sketches, I even felt Kate’s breath on my neck.

On the six-month anniversary of her death, Walter arrived, uninvited, holding flowers and a sympathy card, and I lost the rest of my reserve toward him. I’d woken up raw and angry and unbearably sad, and as much as I wanted to succumb to the pull of flannel and darkness and self-pity, I let him in. Instead of going back to Kate’s office, we sat across from each other at the kitchen table, cupping our hands around mugs of hot coffee, turning our faces toward their aromatic steam.

Without looking up, Walter said, “The first of her books I read was Winter Wheat, my freshman year in college. My professor was a raging feminist, so, you know. But the way that book worked on gender and lineage without working on them reminded me of Twain.”

“Let’s not talk about Kate.”

“Everything we’ve been reading … don’t they want to publish it?”

“She put them in the drawer for a reason, and not just because she was a pack rat. When she died, I found ten years of receipts in her sock drawer. Ten years of receipts for gifts she’d given me.” I laughed, but it felt like glass in my throat. “Let’s not talk about Kate.”

The quiet that followed was dense and uncomfortable. Truth was that I very much wanted to talk about Kate or at least dip into those file cabinets. But what did Walter know about loss like this?

As if to prove my point, he said, “I’ve been applying for grants to pay for gas and some of my time doing this. I know you said there was a lot to go through, but you weren’t kidding. I was thinking that maybe I’ll try to get out of teaching one class this summer so I can focus more exclusively. I should be publishing as I go along, but who’s got the time?”

I searched his face for a deeper meaning beyond this low-level whine. His unkempt stubble and fly-away hair had become familiar to me these past weeks, along with this wide-eyed boyish look, like each moment was surprising in some small way.

“Maybe if I could take some materials home with me. Just a folder at a time so I can start on the letters while we’re still going through drafts here.”

“No.”

“I get it.”

“No. No, you don’t.” My anger wasn’t really anger but a slimy mix of fear, sadness, and fatigue. “You want her letters? Fine. Let’s get to work, then.” I left the kitchen and went to Kate’s office, not waiting for him to follow, but when I opened the door and realized the air inside no longer smelled like her but, instead, of coffee and Walter’s cologne, the grief of the day caught up with me.

“Audrey,” Walter said from behind me. Maybe I should let him take the whole trove of words home, get it away from me, give me a fighting chance.

“Go home, Walter,” I said without turning around.

“Do you mean—”

I sighed. “For today, Walter. Just for today.”

Three or four months after Kate and I found each other, we endured a barrage of inquiries around when we were going to move in together, where we’d live, who was going to give up her lease, which neighborhoods we were considering. One night, when we were at our friends Tammy and Rachel’s house, not long after they’d brought their new baby home, I had enough of the pestering. “What’s the point of being a lesbian if you can’t escape all these rules? I mean, Christ. What’s the rush? Can’t people just date anymore?”

Tammy, who’d known Kate the longest of all of us, shot a look across the table that spurred Kate into evidencing great interest in her asparagus. “Ah. You’re dragging your feet.”

Before she could confirm this terribly accurate assessment, the baby started crying in that short, alarmed way of newborns, his upset broadcast clearly through a monitor on the kitchen counter. Kate launched to her feet. “I’ll get him,” she said and slipped down the hall.

Tammy said, “I’m right, aren’t I?”

I was distracted by the crying too much to lie. “Sometimes I think something’s truly wrong with her. Like maybe emotional imbalance is required to be a writer. The way she can just completely disengage from the real world, be here and not at all here at the same time…”

“She’s crazy about you.”

“Or maybe just crazy?” I asked, half-seriously. The crying cut off as quickly as it had begun, and Tammy and Rachel sagged. I excused myself and went to find Kate, who sat in the nursery’s rocking chair, her head bent toward the infant in her arms, whispering. Seeing her like this, quiet and almost small, removed any last doubt about wanting to be with her, pledging to be with her even if she never wrote another word. At this moment, I didn’t care that she’d ever written a single word to begin with. “We need to talk,” I said.

She put a finger to her lips then pointed at the baby monitor. I crept closer despite my historic unease around children under six, the age at which most of them could read and at least nominally reason. I knelt next to her and whispered, “I’m not on their side, but what’s so wrong with wanting you around more?”

She turned to me, turning with such quickness that the baby stirred and was set to start wailing again before she bounced it a few times and put the chair in motion. Speaking more to the baby than to me, she said, “But you seem so content when I’m not around.”

“If you’re not around, how would you know?”

“You know what I mean.”

“No, actually, I don’t.”

“I’m only a little better than a mid-list writer; I’ve just been lucky.”

“What does that have to do with anything?” It came out loudly, but I didn’t care.

Kate shushed me. “It’s just, a long time ago, I got invested like this but shouldn’t have. I’ve learned how to be content enough, just like you are with your books. I know I’m not good at letting go. When I lost…” she shrugged and bent her head to the baby, her hair obscuring her face. “I lost a lot.”

I wanted to strangle and kiss her, simultaneously. The memory of her tall and loud and vibrant behind the podium layered over her, curled around that innocent baby caught between us, and I lost my senses in a rush of desire. “Books,” I said, fiercely and loud, “are not enough. You think I haven’t been hurt? Don’t be stupid. But you love through it, despite it. What else is there?”

She brushed a finger against the baby’s cheek, which looked as soft as it surely felt. When she finally turned to me, she was smiling in a crooked, sheepish, apologetic way that was so disarming she surely practiced in the mirror. “Nothing, Audrey. There’s absolutely nothing.”

Two months into this spelunking exploration of Kate’s papers, out of loneliness or just plain insanity, I invited Walter to stay in our guest room. My guest room, I reminded myself. I told him I worried about him driving so much, which was true enough that I could ignore any more primary motives.

It turned out, though, that having someone else in the house made me think of Kate even more, her words becoming the centerpiece of every moment. Then we started in on her letters, and in a startling shift, the tower of Babel of her fiction fell away. While the recipients of her letters were spread across a wide range of locations, professions, backgrounds, and personalities, Kate’s voice in them was always the same, as larger than life in the world of thought as she was in the physical one.

These folders hosted alternating processions of letters received—still in envelopes stuck with stamps of varying value—and copies of the letters she had sent out in response. Photocopies, computer printouts, hand-written duplicates on white scrap paper, smeared purple mimeographs. Even as she sent her words all over the globe, she couldn’t bear to part with them.

I succumbed to the pull of Kate’s voice, especially in dialogs that went beyond research into the personal, even taking them to bed with me to savor them well into the wee hours. In the next room, I could hear Walter typing hard on his laptop, the keys surely shying away from every stroke, and I knew that Kate was with both of us.

One Saturday, we sat in her office, sipping our morning coffee and reading, always reading, and I slid open the next file drawer in our exploration and saw it, a thick sheaf of yellow paper tucked, misfiled, between two folders. I froze. Kate never misfiled anything, and she used notepaper like this for first drafts only, never letters. She claimed to like how the color sometimes clashed with her ink, a result she called “an inspiring ugliness.” But she never wrote first drafts for letters. And she never left papers misfiled.

I stood in indecision for so long that I felt Walter watching me. I turned my back to him and slid the papers free. The date at the top of the first page was years before we met. “I thought about you the other day,” it started in a bright blue ink, “and I got angry out of sheer habit, furious at this weakness of mine, this problem of you I can’t seem to solve like some tricky turn of phrase. Then I stopped, just like that, and I wondered what moronic asshole declared that thinking of someone so thoroughly lost was wrong.

“So, I decided to write to you … but not really. Even if the urge to send this captures me, the effort it would take to discover your address would be enough to put a halt to it. It’s a perfect arrangement. Safety tinged with the thought that you might someday, through some odd set of circumstances, actually read these words. I wonder what you’d think.”

What was this? A letter, certainly, despite the lack of a name at the top, despite the color. I hefted the thick sheaf—equivalent in length to a short novel. Then, in a move I was sure had Kate turning in her grave, I flipped to the end. Although I was just looking for a date on the last letter, my eyes couldn’t help but pick up a few phrases: “never leave me,” “wish so much,” “never had the opportunity.” The date was almost exactly a month before she died.

Behind me, Walter shuffled pages with a sound as familiar as morning bird-song. I slid the stack of yellow paper into the nearest file folder of letters, tucked it under my arm, and took my usual position in an armchair in the corner I sometimes used to sit in when Kate worked in the evenings.

He said, “That’s a big one. Who’s it with?”

I looked at the label on the folder. “Marianne Deurault.”

“Who’s she?”

I shrugged. “Before my time.”

“I still can’t believe she wrote to Taylor Carpenter. The Yankees? An all-star shortstop? Listen to this: ‘What I’d most like to know about are the currents that course through you when you’re expecting a slider, low and outside, or when you notice a batter taking an open stance and drift to the right to cover the gap (I’ve absolutely seen you do this, and it’s the height of impressiveness). When I get an idea, I sometimes mistake it for heartburn; it’s an uncomfortable gnawing, a feeling of unresolvedness without anything as handy as a referent.’ Really? Referent?”

“Yeah. Kate had a way with words.”

He laughed.

“As, apparently, do I.” I opened the folder in my lap, hiding the canary-yellow pages behind thick manila, and picked up where I left off.

“I have made you into a character as fictional as my own but more dear to me—if that’s possible. I know very well it isn’t to you that I write but instead to my idea of you, but I can’t help but wonder how far from the truth that idea is. It comforts me to think that I know you.”

I got sucked into these letters as quickly as into one of Kate’s novels. Though they were spaced months apart, they had the feel of an irrepressible blurt. Kate had apparently met this person in college when she was just twenty, though she didn’t detail the circumstances. Kate at twenty was a thought I had to caress for a long while before I could put it aside. She’d seemed so very herself at forty, when I’d first set eyes on her, that it was strange to imagine her with only half those years, no streaks of gray, a tighter and sleeker body, and no laugh lines around her eyes and mouth.

A couple dozen letters in, I appeared on the page. “I’ve met someone. Zing. I felt it, and it surprised me and then scared me half-to-death. I jumped in, braving loss and traumatic repercussions, but now here I am, scratching out this letter because you have invaded my mind like an avenging angel. What am I going to do with you? How am I going to tell Audrey?”

I remembered the night Kate “jumped in,” a month after that dinner at Tammy and Rachel’s. She showed up at my door, flushed and smiling, dark hair windblown. She hovered just outside the threshold, said she felt twenty again, then in a move steeped in atypical shyness, offered up a ring—the same one still welded to my finger. I yanked her inside, and the kiss that followed, searing and final, was one of my most precious memories.

Twenty again. The reality of these letters, what they meant to Kate for all those years, began to sink in. I weighed the stack still in my hands then riffed through it. When I glanced up at Walter, he was watching me, and I felt like I’d just woken from a book five bus stops past my destination, other passengers staring. Oh, I was caught—on so many levels, too. Not only with these letters but also with my abandonment of getting beyond Kate’s death in any way. Just like she couldn’t get beyond this lost love?

I couldn’t think about that. Not now, not with Walter watching. As if to underscore his scrutiny, he asked, “Are you okay?”

I closed the folder, trying to minimize its existence. “I’m … I need some air, I think. I shouldn’t be here,” I added before I could stop myself, but it was true. These letters in my hands were one thing, but hanging on to a ghost like I was doing? “I need some air,” I repeated, but instead of opening a window, I disappeared to our bedroom (my bedroom) and tucked the papers in the drawer of my nightstand.

Then I hurried to the front door, desperate to escape this futility of grief. I kept my foot on the gas until, after a long, meandering route, I was in a random small town, sitting in a corner of its public library, reading Hemmingway with an unbecoming desperation. He was the writer perhaps the most unlike Kate. Spare, masculine, deadpan. I longed for him to spirit me from my life in a way he’d never managed to before, and he failed me again this time.

This was not at all what Kate would want. She’d said it in so many words at each of our anniversaries. “You do realize that I’ve ruined you forever for a life of the mind. Once you’ve loved like this, you’ll never be happy with just books again.” What she’d neglected to mention was the high likelihood that no one else could ever come close to filling her size-ten shoes. She’d scoff at that, but the reality was that I might live another twenty years without her, and though I still couldn’t conceive of her permanent absence, I knew without a doubt that I’d love and miss her until my last breath.

Clearly I had to get all those papers out of the house. After that, if loneliness and heartbreak had their way with me and left me still alive, which was what was purported to happen, I would decide about the rest of my life then.

When I got back, the house was silent as a grave, not even broken by the hum of the refrigerator. It even felt darker than usual. I stood in the foyer for a moment, letting my eyes and ears adjust. “Walter?” I called even though I didn’t remember seeing his car at the curb. He was out, blowing off steam like I always told him to do, but even as I thought that, I navigated the dark hallway to Kate’s office. I turned on the light and saw a short stack of paper on the desk with a note sitting on top. I was drawn to it with a cracking, dreadful inevitability.

Of course it was those letters—it couldn’t but had to be at the same time. I snatched the note off the top before confirming my suspicions. It read: “Audrey, I’m not sure if you’ll hate me or ultimately thank me for what I’ve done.”

I stopped reading and levitated to the file cabinets, yanking open each drawer in turn. By the time I’d peered into the empty, black depths of each, I was shaking and breathing hard, making noises that didn’t resemble sounds I was even physically capable of producing.

I lurched back to the desk and willed my eyes to focus on the note, to decipher Walter’s scratchy cursive. “Not long after I started here, I paid a lawyer to look over our agreement, and while you could seize the writing from me, I’m still allowed full access, including copies. Maybe you can be a little happy to have enabled a career for me—and ultimately let readers know the real Kate.

“I can see you tried to hide these from me for good reason. I doubt you made it all the way to the end earlier today, but you were right as to their importance. I feel I owe you the originals, but I took copies. Fantastic!

“Thank you from the bottom of my thieving heart. Walter.”

My brain wasn’t functioning correctly, fizzed and popped around words and visions and emotions, leaving me only enough solidly connected synapses to wonder if I were having a stroke. I collapsed into Kate’s chair, yelled, “Mother fucker!” then clapped a hand over my mouth.

Through the shocked static in my mind, I wondered why Walter mentioned the end of these letters. They weren’t a book. There was no plot, no pending resolution outside of Kate’s death, but his words bothered me enough to thumb through the stack to where I’d left off, to Kate’s proposal, and start in again.

I appeared on these yellow pages on and off over the years—always with love, but always, always, with the mention of the secret she kept of this communication. “I wonder so much what you and Audrey think about me. You more than Aud because she’s here to ask in the wee hours of the morning when my self-assurance wanes like my metabolism. But even then, I’m all-too aware of the things I haven’t told her. You, for example. What would she think of me if she knew about you—not just the past but this strange sort of present I force into existence?

“And you, I wonder what you would think if you could read these letters and know that I have always continued to hold you in my heart as I suspected I would.”

In these letters, I saw story and novel ideas take hold and get fleshed out, skimmed over whole paragraphs of essays she’d later published, and wondered what came first, the letter or the “real” first draft. Later, I relived those years when Kate became ill and realized she wasn’t going to bounce back. While her handwriting proceeded unchanged, her tone was subtly altered, and it made me hurt all over again, remembering her slow but steady decline. She wrote as much as she could but was often frustrated by physical fatigue affecting her mental prowess.

I remembered the day I understood that she had resigned herself to death. We were sitting across the kitchen table from each other, and out of the blue and in a way that stopped any thought of further conversation, she said, “I think I’m going to stick to short stories from now on. Maybe even poetry.” I excused myself as quickly as I could without being obvious, went to the bathroom, turned on the taps, and cried until my head pounded.

Then the last letter. I didn’t want to read it, wanted to save these words to know there would always be more of Kate still left to learn, but I was a reader as much as Kate’s wife, and I had never, not once, stopped this close to the end. I promised myself to go slowly.

“Even after all these years, I still haven’t explained, have I? Maybe you were never told that you were adopted, that someone, me, had given you up mere minutes after bringing you into the world. But you were, and I did, and my darling boy who I’ve never known, I still don’t know what to think about that.”

My ears roared. Literally. They were filled with a rolling white noise, and my assaulted mind could not be stopped from thinking that I’d always scoffed at that description in books, always considered it a lazy cliché, but it was absolutely true.

A baby? A boy? Kate had mentioned she’d been with men when she was young and stupid—hadn’t most of us?—but a baby? A boy?

I read on, gulping down the words. “Your father was at least partly right. Keeping you would have been a mistake—maybe not the disaster he predicted and certainly harder than I imagined—but I still can’t conceive of aborting you. Our child? A child of love? Because I did love him. Enough to lose my senses at least a little.

“At the hospital, your new parents were waiting. I could feel them around the ragged edges of pain and sadness and grief and a thousand other things. They were there, and he wasn’t, and all I could do with that was breathe and push and breathe again, whatever the nurse told me to do, whatever the doctor asked. While the labor progressed, I made sure everyone knew I didn’t want to hold you or see you. I didn’t want to change my mind. Couldn’t. Probably wouldn’t, but I couldn’t risk it.

“Eventually, you cried, and I cried, and I found that I had to know, so I asked, and they told me, and you were a boy. A healthy boy who is now 42, if nothing terrible has happened, who has lived a life I have no way of imagining, let alone knowing.

“All this time, all these words between then and now, and I’ve never once written of it, not even written close to it. These letters to you, this graven image of you I’ve been directing these words to, this muse I’ve made you into—let’s be honest. I eventually forgave your father, even forgave myself, but you will never leave me, not that I want you to. I keep you close, secret, so that you can’t escape despite how I let you go, so that I can keep you safe in a way I never had the opportunity to.

“I wish so much that I could have known you.”

I put the letter down and cried like I hadn’t since the night after she’d died, when the relief of her being past her suffering and the numbness of shock both wore off. I was so wretched and thorough in my sorrow that I slid from the chair and was huddled half under Kate’s desk by the time I calmed. My chest ached, and I was afraid to move, knowing the contraction of muscle would shake loose thoughts I wasn’t sure I wanted to think.

I rotated my wrist just enough to see my watch—nearly two in the morning—and that was enough. Why hadn’t she told me? Did she not trust me? Was she ashamed? She didn’t sound ashamed. Resigned, maybe. Sad but not really regretful, not about giving up her son and not about keeping this from me.

The betrayal of this secret made me feel, finally and completely, the betrayal of her illness and subsequent death, of her leaving me too young after too little time together. Then, not only leaving me like that but leaving me with this. In my anger, I got up to find Walter, to spew vitriol at someone who might have the vaguest possibility of understanding, and I remembered the empty drawers and the jocular note. There they went again, my ears, and in their din, I imagined Walter’s first article, the follow-on book, a tour that could wash me up at his signing table where I’d bash his teeth in.

I was shaking, punch drunk, ears not roaring anymore but ringing in the heavy cotton batting of quiet in the house. Yet just to the side of my stunned fury was a resonance of loss, and I thought I could feel a little of what Kate had felt in that delivery room, an emptiness terrible and final, an acceptance of facts long gone unacknowledged in just this way.

I hated so much that Walter knew this about Kate before I did. But, even more, I hated that I never had the chance to hear her talk about this directly, to let her lean on me in memory. I hated that Kate didn’t have the courage to expose this old hurt. She played the big-boned gal with the corn twang perfectly, but the only way she could tell me about this was by leaving these words to be found by whoever came along.

She was well and truly gone to me just like her son had always been well and truly gone to her. All I had left that I could put my hands on was this stack of yellow paper. I weighed the sheets in my hands, wanting so much to make my own idol of them, to imbue them with a Kate still somehow alive. It would be so easy to slide them back in the drawer of my nightstand, read a page every night, and go to sleep with Kate still curled around me.

Instead, I got up and went to the living room fireplace. I tossed the papers onto the hearth, fished out a long match, and struck it against the stone. I sat for a minute working up the nerve, the flame devouring the match little by little. But when the corner of the stack curled up and blackened, my heart seized. I lunged in to grab the papers, and my hand jerked back, singed.

Then, just as I was going to cry, I started to laugh, instead. Christ, Kate, what an unbelievable mess you’ve made, keeping this to yourself for so long only for it to escape so completely. She’d managed to let go of it, somehow, releasing these singed and curling pages to fate, Walter’s hard drive, and our fireplace, and all that was left for me to do was the same. Let her go. Watch this part of her burn and find some kind of freedom in it.

Amanda Kabak has had stories published in Midwestern Gothic, The Quotable, Perceptions Magazine, and other print and online periodicals. She won the Betty Gabehart prize, issued by the Kentucky Women Writer’s Conference, was a finalist in december magazine’s Curt Johnson prose contest, as well as the Iron Horse Literary Review chapbook contest, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her first novel is forthcoming from Brain Mill Press in 2017.