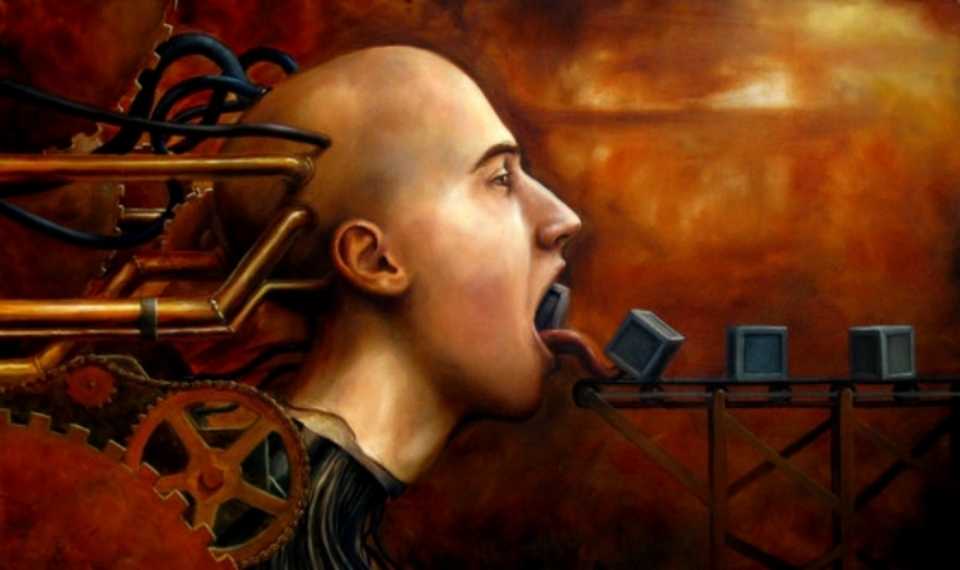

“Idea Machine,” oil on canvas, by Ryan Ayers, 2008. Used with permission.

Madam Chairman, members of the Organizing Committee of the annual Werner Kulm Conference, respected members of the Academy, and esteemed colleagues, I am profoundly honored by the invitation to deliver the keynote address to you this evening and will endeavor not to make it overlong.

You will appreciate that the title of my lecture is ironic. As yet, there has been no last philosopher, nor do I think there is likely to be one. I agree with Søren Kierkegaard who wrote that, humanly speaking, each generation must begin afresh. This means that we must not only learn for ourselves how to breathe and love and age, but must take our own stabs at answering philosophy’s questions. Each generation begins by gnawing on the bones of its forebears, as Kierkegaard himself did on Hegel’s. Perhaps what infuriated Kierkegaard about Hegel was that he was the sort of philosopher who really would have liked to be the last.

My lecture will be concerned with another pair of European thinkers. Naturally, my chief subject will be Werner Kulm but I will also have something to say about Karl Waisenhaus, who laid so relentlessly into Kulm’s work.

According to his older sister’s notes for an unpublished memoir, as a child Kulm was often solitary though seldom lonely. “During our years in the big house in Kaiserslachen,” Charlotte writes,

Werner’s brightness prevented him from getting on with the other boys; he was impatient with them and they taunted him. Of girls he was frightened while grown-ups were frightened of him. Between the ages of seven and nine my brother kept company with the characters of his marionette theater, a Christmas present from jolly Uncle Adalbert. Though Werner gave up in frustration after a few half-hearted attempts at making the puppets move, he liked to fashion costumes for them, with my help. He would sit them down or prop them up and stage conversations among them. Sometimes he pretended they were people we knew or figures from history, like Frederick the Great and Bettina Brentano. At other times Werner cast the puppets as imaginary people with droll or pompous names, such as the Graf Pharmacopia von Schwarzmastdarm.

With admirable understatement, Charlotte writes, “My brother was exceptionally advanced in his reading habits.” She recalls happening on him in the nursery one afternoon as he conducted a dinner party for his puppets. He had placed four of them around a miniature table.

He used one of Father’s old handkerchiefs as a table cloth. When I asked who the diners were he pointed to each. ‘That one’s Bertrand Russell, she’s Hildegard von Bingen, that fellow with the cotton-wool beard is Martin Buber, and the good-looking lady over—that’s Héloise, you know, from Peter Abelard.’ So it was boy-girl-boy-girl, modern-medieval-modern-medieval. ‘Be quiet, Lotte. They’re talking about God,’ said my brother in that way he had even then of being solemn and mocking at the same time.

According to his sister, in later years Kulm dispensed with the marionettes, but continued to conduct what she calls “imaginary parliaments,” with heated debates in strong language. Before their parents became accustomed to their son’s habit of talking to himself in different voices, she says, they feared for Werner’s sanity.

It seems to me that the exceptional comprehensiveness and profundity of Kulm’s mature thought owes much to these childish confabulations. It as if he were able to be more than a single person, yet without ever losing the integrity of remaining Werner Kulm. Yes, I think that Kulm’s greatness derives from this ability to be many people, to fashion, so to speak, a multifaceted mind, his unique e pluribus unum.

*

I hope you will pardon me if I now speak of some elementary matters.

There are only three kinds of questions in the world. First, there are questions like: when will this lecture end or how old was Werner Kulm when he gave up playing with his puppet theater? These questions are about matters of fact, the kind historians and scientists investigate. They are called empirical questions after empeirikos, the Greek word for experienced, because they can be resolved by experiment or by experience. Do you prefer green or black olives? What color is an orange? Who won the Peloponnesian War? All these are empirical questions.

The second category of question is called formal. How much is two plus two? If the left fielder catches a ball before it hits the ground is the batter out? If a staid language philosopher drives south from Harvard at 55 mph while a suicidally lunatic aesthetician heads north from Brown on the wrong side of Rte. 95 at 120 miles per hour, where will they meet up? You don’t answer formal questions like these by watching baseball games or checking the historical record or crashing cars; you get the answer by following certain pre-established rules, like those of logic, math, and baseball.

Now, of course there are clear methods for finding answers to empirical and formal questions. And if you can’t find the answer on your own, you can usually track down an expert who can give it to you and show you why it’s right.

This is not true of the third type of question, though: philosophical questions. Here it is not at all obvious how to find an answer nor even where to look for it. What is justice? How should people be governed? How should happiness be defined? Is there a human nature? Is anything good-in-itself? How is it that we know things?

Such questions are not pointless or impossible to answer; on the contrary, it is precisely because there are so many answers to such questions that it is easy to assert that none is final, even for the experts. Still, a multiplicity of answers is not enough of an explanation for philosophy’s lack of conclusiveness; after all, I can conceive of an infinite number of answers to the questions of how much two plus two makes or who founded the Academy. All but four and Plato would be incorrect. So is it really the case that no philosophical question can be finally and conclusively answered? And if so, why?

It might be argued that any question that can be finally answered would not be a philosophical one, that a philosophical question is simply and essentially one that cannot be finally answered. On the other hand, it could be said that only one thing is necessary to make a philosophical answer final: that everybody should accept that it is so. For most cultures at most periods this is pretty much the case. Those who dissent are regulated by self-censorship, exile, re-education, ridicule, or martyrdom. The obvious riposte to this position is that such coerced conformity is limited by time and culture and that, anyway, conformity is not identical to conviction. Still, there is something unsatisfying in the tautological view that no philosophical question can be finally answered because if it is really a philosophical question then no answer can ever be accepted as final, except by those propounding it and perhaps not even by them.

So let us suppose something different, namely that philosophical questions are not conclusively answered because we don’t want them to be. If it were a matter of a medical diagnosis the opposite would be true. Too many answers to the question, “What’s wrong with me, Doctor?” are as good as none at all. But with philosophical questions the opposite seems to be true; a single answer, delivered with finality, makes us suspicious and provokes us to rebuttals and objections. It would be surprising if the philosophers who supply such answers did not themselves know that, while their answers must be presented as final, they will not be final. Even the relativists, who might be expected to proclaim the provisional nature of their relativism (“it suits our times” or “this is just the way things seem to me now, at ten a.m. on Tuesday morning”) —even the relativists sound absolute about their relativism.

If there is such a thing as a weariness with philosophy’s inconclusiveness, a taedium philosophiae, then it may have reached its zenith with the Vienna Circle and the natural language philosophers of the early twentieth century. In their respective ways, these exasperated thinkers tried to draw a line under old-fashioned philosophical speculation, annihilating philosophical questions simply by declaring them meaningless—meaningless precisely because they are incapable of being answered with finality. Of course, they failed because their arguments, intended to put an end to philosophical argument, ironically became another episode in the long argument that is the history of philosophy, no more final than what they attacked for not being final. Worse, they began the growth of a new branch on the tree they wanted to cut down, filling up the professional journals and the minds of graduate students with the speculations of a new meta-philosophy.

Nevertheless, many people, even those who are not graduate students or professional philosophers, are dismissive of philosophy on the ground that any answer to a philosophical question is no more than a matter of opinion, relative to the point of pointlessness, perhaps important to the individual who delivers it but equally irrefutable and unverifiable. Nevertheless, our species devotes a lot of attention and considerable prestige to philosophizing and grants the status of great philosopher to few human beings, to far fewer than, say, poets, musicians, or athletes. This would be odd if the answers to philosophical questions really had no importance, no practical worth. But they do have such importance and worth. To live, we human beings require at least provisional notions about ethics, government, friendship, knowledge, logic, and aesthetics. It seems to me that thinkers, cultures, and eras are not distinguished so much by posing novel philosophical questions as by embracing new answers to the perennial ones.

No, the simplest hypothesis is the best: people do not want final answers to philosophical questions. And by people I mean philosophers. One might almost think that what is essential to them is not the triumph of their own ideas—though they certainly write that way—but that the conversation continue.

Picture a great philosopher, another Kant, a man who has answered all philosophical questions not only to his own satisfaction but to that of virtually everybody else. How long would it take such a genius to feel this comprehensive triumph as a catastrophe? How would he respond as he watched the discipline he loved wither before his eyes and because of him?

This brings me back to our subject because I submit that Werner Kulm was just that philosopher. Another Kant, a latter-day Aristotle—these are the epithets and comparisons he evoked in his contemporaries. How would Kulm have reacted to such a situation? How would the man who spent years of his childhood as Kulm did putting clashing views into the mouths his puppets have responded if not dialectically? The needful thing to him, I submit, would have been to undermine his own victory, to do what none of his contemporaries was capable of doing with any success, which was to question the brilliant and convincing answers to the questions of philosophy given by Werner Kulm.

You might say that, even if I am right, Kulm could simply have chosen to revise his ideas, but re-pointing the bricks only confirms the structure that is already there. What Kulm would have wanted was a wrecking-ball. And since the questions he answered to everyone’s satisfaction really were philosophical ones, this would not have been hard for him to do. The only surprising and unprecedented thing is that he should have to do it himself, philosophers being, if you will pardon me for saying so, notoriously contentious, envious, and disagreeable people. Yet had Kulm at the end of his career attacked his own ideas this would have caused consternation, raising the suspicion that he had been playing games all along or, worse yet, that the certainties on which his contemporaries were blithely proceeding with their lives and the finality for which they had thanked him with forty-three honorary degrees and a national medal, by attaching his name to five boulevards, three comprehensive polytechnics, two parks and one frigate was just a cruel illusion. People would be justifiably indignant with him if they thought Kulm had compelled their belief in his ideas without believing them himself. That sort of thing leaves people feeling foolish and cheated and with no way to regard their ex-master except as a confidence artist.

There was also his vanity to consider, the fulfillment of his ambition. After all, his name had become an established adjective and remains so to this day: Kulmian minimalist logic, the Kulmian maximalist imperative, Kulmian analytics and dynamic method, etc. He who had set out with the hope of someday being among the philosophers—as Keats wished to be among the English poets—had superseded them all. But at what price? He had done what Wilde said all men do—killed the thing he loved. What Kulm had killed was love itself, philosophia, the love of wisdom, because what is finished really is dead, even should it be as perfect as a diamond.

And so, I submit that Kulm did the logical thing. He invented a pseudonym, a puppet, to demolish his own ideas. I like to imagine it was with joy and real relish that he reversed his initials and wrote as the obscure and parentless Karl Waisenhaus. In the series of critical articles with which you are all familiar, inventive vituperation and self-mockery erupted and hot lava flowed over the whole terrain of his life’s work. As Waisenhaus, his last marionette, he opened up all the doors he had with astonishing brilliance and infinite pains, as Kulm, closed. He must have felt like the hero in the childish old Westerns who, having established civilized order, turns his horse’s head toward the setting sun and the lawless frontier. Love, he would have thought to himself, is more verb than noun, philosophy a thing you do rather than a doctrine you have.

As you know, I am the official editor of Kulm’s papers. Among them, I found a sort of preface attached to offprints of the first five articles of Karl Waisenhaus. It is written in Kulm’s own hand and begins with this sentence: “I will make him twenty-five years my junior, fierce and unrestrained, a hungry lion keen to gnaw on my flesh and bone.”

Thank you for your attention.

Robert Wexelblatt is professor of humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies. He has published essays, stories, and poems in a wide variety of journals, two story collections, Life in the Temperate Zone and The Decline of Our Neighborhood, a book of essays, Professors at Play; his novel, Zublinka Among Women, won the Indie Book Awards First Prize for Fiction. His most recent book is a short novel, Losses.