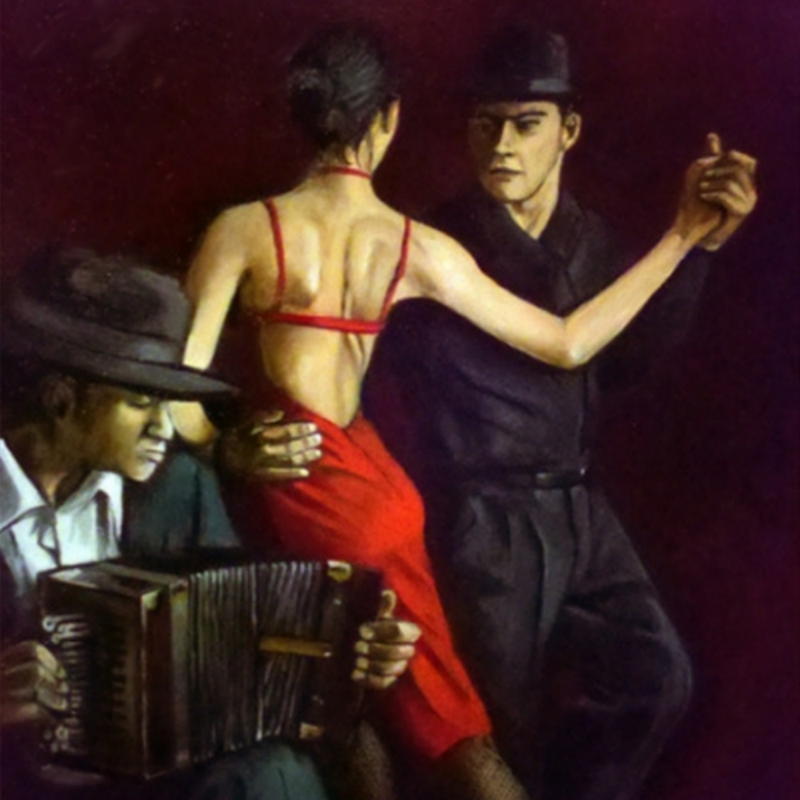

“Dance at the End of the World,” oil on wood, by Joel VanPatten, 2012. Used with permission.

The windows are open to the blue-black sky, but there is no breeze to move the heavy air inside the apartment. Across the street, the diner blinks its electric blue sign. EAT, it urges. Eat, Ana repeats to herself, only to practice her English vocabulary, knowing that the craving she feels is not for food.

She sits rocking, the squeak of the chair chorusing with the sucking of the baby at her breast. She strokes Carmela’s head as she turns to watch Rudy. He’s in front of the bathroom mirror performing—yes, she thinks, performing—this Saturday night ritual, begun in the months after Carmela’s birth.

He’s wearing just his underwear. His suit hangs smartly on the hook of the bathroom door, the stiff creases in the trousers giving them a look of alertness, as if wary of Rudy’s muscular body. Rudy leans over the bathroom sink, inches from the mirror. He stretches his upper lip down over his teeth, snips at the hairs of his elegantly thin mustache, retracts his mouth in a smile. He rubs hair cream in his palms, sniffs at its glistening whiteness, and then massages it into his black hair one, two, three times—a calisthenic that works the muscles in the taut curve of his arms and shoulders. He swigs mouthwash from the bottle, and then, posed like a garden statue, spits like a fountain into the sink. With rapid hands, he spanks his face and throat with cologne. Invigorated by the self-administered slaps, he draws himself into his fighter’s stance, bounces on the balls of his feet toward his reflection and protects with his left while he delivers several mock blows with his right. Then he whirls to spar with his suit hanging on the door. Prevailing against both opponents, he leaps into the middle of the room, arms raised above his head in victory, and Ana, still watching, makes her mouth smile, while something clenches in her throat.

Perhaps it is indigestion, after all, this feeling that squeezes against her belly and throat, and makes it difficult to breathe.

Heartburn, indeed, had been Irma’s mocking reply when Ana had foolishly related her symptoms to her cousin. Irma, ten years older than Ana and married to a silent and featureless gringo, had taken Ana in when she first arrived in Kimball Park. And though Irma had appointed herself chaperon to Ana, following her conduct with a severe eye, Ana had not left the dusty streets of San Blas to be smothered by her cousin’s conventions.

Within a few months, she had met Rudy at a Saturday night dance, and in front of Irma’s reproving stare, Ana followed the lead of Rudy’s smooth, confident steps, responded to the press of his hand at the small of her back as he steered her left or right, answered the cue of his fingertips as they spun her away and then reeled her back in.

In between dances Ana learned more about this dashing young man because Rudolfo Luis Borrego spoke as charmingly as he danced. First of all, he liked to be called Rudy, as in Rudy Vallee, and he crooned an imitation of the singer. He didn’t mind being called Rudolph, though, as in Valentino, and he struck a swashbuckling stance. He said he was a painter, and Ana imagined canvasses filled with passionate strokes of color until Rudy laughed and said, no, he painted buildings—tall ones. But his real profession was boxing, and he bounced back and forth on the balls of his feet to demonstrate and then gracefully slid into a foxtrot because, he explained, dancing was an extension of his athletic training. Then he winked, adding that dancing was also romantic, especially with a partner as beautiful as Ana, and he took her in his arms and guided her effortlessly, in command of the music, in command of the other dancers who yielded the floor and the onlookers who watched with both envy and appreciation, and in command of Ana herself who surrendered to the fast-slow-fast-slow sway of Rudy’s foxtrot.

As he dresses, Rudy hums the popular songs of the day, inserting words here and there to display the progress of his American accent to Ana, who clings to her Spanish language as if it were a shawl cloaking her from the cold. Rudy wriggles into his jacket to the beat of the song he is humming, and then executes a few dance steps, again with his reflection, this time in the window, the neon blue of the diner sign flashing on his strutting figure.

“I can come if you’d like,” Ana offers, though her clothes feel untidy and the pull of Carmela’s mouth draining her breast makes her drowsy.

“But Ana,” Rudy scolds only half playfully, “you don’t like the fights.”

He takes it personally that she doesn’t like boxing, doesn’t see the art in it.

“And besides, what about the baby?”

She holds Carmela up as if to say our baby. Rudy steps up, coos at Carmela.

He is delighted as she throws her tiny fists at him and works her mouth in circles bubbly with saliva. “A fighter,” Rudy laughs. “Just like me.”

She pulls Carmela back. He drops a kiss on the braid wound in a knot at the back of Ana’s head.

“Who’s fighting tonight?” she asks, as if it matters to her.

“Jimenez and the Turk.”

It is not Jimenez and the Turk for whom he dresses so fancy. It is for himself. But as long as he is dressed so prettily, it should not go to waste after the fights, and Ana knows he will stop at the dance hall afterward.

“What time will you be home?”

“Late. Get your rest,” he tells her, as if it matters to him, she thinks. He disappears behind the flimsy door of their one-room apartment. But the smell of him lingers on—a bouquet of hair cream, mouthwash and cologne. Ana disperses it momentarily with a sigh.

She listens as his footsteps fade down the stairs, hears the slam of the street door shut them out completely.

She remembers the pound of her own footsteps the day she ran to meet him.

The South City Athletic Club, he had said, importantly, as if it were a famous landmark. Nevertheless, he drew a map on the inside of a matchbook.

When she arrived, she was breathless from the walk, the distance longer than she had counted on. There was sweat at her temples and at the nape of her neck, places Rudy’s fingers had grazed as they danced the night before. She dabbed at the moisture on her face with the back of her wrist, lifted her long hair and fanned herself with her hand. She worried about her appearance, how her ruffled hair and damp skin could make her seem careless.

She paused at the door to the gym. There was a sign that she couldn’t read, except for the word NO, and this was enough to stop her. She didn’t know what to do next. She took the matchbook out of her pocket and looked at it again.

NO had seldom stopped her before. But NO surrounded by as yet mysterious English words made her shy, even with a door. She backed away to look for another entrance that might not have the word NO on it. But once she turned the corner and down the alley, she had to look no further. She came upon a small yard, an outdoor extension of the gym where several young men were engaged in various boxing exercises—punching a bag or sparring with an invisible opponent. Against a low brick wall a collection of women lounged attractively to admire the sleek fighters wholly intent on their workout as if unaware of their audience.

Ana understood that was where she was supposed to go, to sit with the other spectators, but she would not do it. She had not come to this country to be a spectator to someone else’s life. Yet she watched. Saw him dance, lithe and quick, evasive when necessary, attacking when he saw an advantage. She waited for Rudy to notice her, and when he didn’t, she both fumed and felt forlorn as she turned to walk away. She had just rounded the corner when she heard Rudy call her name. It was almost a bark. And yet she did turn around, because there was a pleading inside his gruff command. She watched him trot toward her in his singlet and shorts, his hands still encased in boxing gloves, the bare portions of his body—his arms and legs and a swath of chest—gleaming.

“Why are running away from me?” he called.

Ana, who believed her life was not about running away, but running toward something did not answer, because she also did not believe in raising her voice in public. Rudy though was not concerned with the eyes that followed him down the street. He’s a spectacle, she thought. A beautiful spectacle of a man. So when he asked his question again, instead of saying proudly, I’m not running, I’m walking away, she told him “You were occupied.” It came out apologetic (as if she were somehow at fault), instead of reproachful as she meant it to be. But it sent Rudy to his knee and Ana’s will to a gentle gust of wind.

She didn’t like the actual fights though. Fighting as sport didn’t make sense to her. The first time Rudy took her it was to watch a fighter whom he would face in the ring the following Saturday. As Rudy pointed out his soon-to-be opponent’s strengths and flaws, Ana could feel the energy of his body, the intensity in his eyes, the readiness in his fists.

Ana closed her eyes each time a fist made contact. She wanted to cover her ears against the urgings of the crowd, through which a grunt or a groan from one of the fighters could be distinguished.

“Next week, you’ll see me in there.” Rudy said.

He said it as a certainty, and Ana wondered how he knew she would come.

He saved a place for her in the second row, just to the right of his corner, so she would always see him at least in profile. She covered her face at the bell.

She found herself trying to defend the sport to Irma and her husband Donald.

“It’s an art,” Ana told them. “There is beauty in the movements.” She had rehearsed the words that Rudy had so often given her, and though she could say them without error at Irma’s dinner table where English was the rule, they sounded flimsy. Weightless.

Weightless is how Ana feels as she sits in the rocking chair alone, Carmela asleep in her crib, in the one-room apartment above the corner market. Here in this California city, the limits of her world are fixed by newspapers that she does not read because the headlines in English baffle her, by street signs that are unfamiliar beyond a few blocks, and by conversations that rush past her undecoded in the aisles of the market downstairs—sounds that are bland and indifferent, like the bread she buys there.

Ana stands up and begins to pace the room slowly, stopping now and then at the window to look beyond the blue sign of the diner to the community hall. All she can see is the roof, but she knows that the windows blaze yellow with light and inside, sweating couples dance as if their lives depend on it. And she knows that Rudy is there, dancing with first one and then another of the partnerless women that line the wall near the punch table, fingering the glass beads at their necks, gazing with practiced nonchalance at the pairs of lilting bodies on the dance floor. As she paces the room, Ana hears Rudy’s voice remind her that dancing is essential to his profession in the ring. It keeps his reflexes responsive, rehearses him for a fight.

She continues to walk the perimeter of the room and with each turn she quickens her pace, and as the room begins to shrink she remembers how she used to walk the plaza in San Blas until, finally, she resisted those boundaries, making her way north on a slow, crowded train to end up here in Kimball Park in this apartment above the corner market. And the memory of why she came makes the disturbance she has felt in her stomach disperse to her limbs. It clenches her fists, makes her feet jittery with energy.

Ana lifts the sleeping Carmela from her crib, descends the stairs, lets the door slam shut behind her. She tucks the ends of her shawl around Carmela, though outside the night is warm and embracing. She crosses the street, passes under the cool, blue wink of the diner sign and as she turns the corner to the community hall, she can already hear the music. She enters the hall and pauses, lets her eyes take in the pair of potted palms that curve dreamily at each end of the stage where the band, its members dressed in matching powder blue jackets, delivers a tune brassy with jazz. She scans the dance floor, restless with the undulations of entwined pairs, and in the middle is Rudy, limbering his muscles, timing his reflexes for his next fight, swirling an orange-chiffoned brunette, and not yet seeing Ana until she is within an arm’s length of him and his partner.

He looks at her with alarm and tries to chase her away with his eyebrows, bushy expressive caterpillars that no matter what their message seem to Ana terribly persuasive. But the bundle in her arms squirms and Ana is emboldened. She stands her ground. Rudy takes his rumba in the opposite direction. He’s ignoring her now, wants to avoid a scene by pretending he doesn’t know her. He has so deftly guided his partner that she is so far unaware of Ana and the baby she holds. But now Ana inserts herself in the space between Rudy and the chiffon lady. Before the chiffon lady can react, Ana is thrusting her arms out, displaying the swaddled Carmela who is awake now, her black eyes quizzical, a spit bubble emphasizing the O of her mouth. The chiffon lady recoils and recedes into the crowd around them which has stopped dancing though the music continues. Ana is glad for the music, for the blare of the horns and the crash of the drums, which makes it difficult for any words to be heard. But words are unnecessary. She turns to Rudy who is smoothing his mustache, trying to hide his astonishment at her trespass into his territory. Yet she doesn’t claim her dance. Instead she carefully lays Carmela at his feet, at his shoes with their high sheen. She walks away, through the parting, gaping crowd, trusting, knowing Rudy will follow.

*

Rudy always sleeps late on Sundays. He sleeps heavily. There is barely a trace of the cologne he slapped on himself last night before he left, barely a trace of the smells of crowded places—gin, sweat, cigarettes, chiffon-clad ladies. It has been obscured by the stale air of the apartment. By the odor of her own skin.

Ana sits in the rocking chair, Carmela in her arms, and watches Rudy. Outside, the diner sign is unblinking in the daylight. She closes her eyes, alert to the slightest noise, the merest change in temperature, the tempo of breathing.

Donna Miscolta is the author of When the de la Cruz Family Danced, published by Signal 8 Press in 2011. Her work has appeared in Hawaii Pacific Review, Connecticut Review, and elsewhere. Awards include the Bread Load/Rona Jaffe Scholarship for Fiction, and grants from 4Culture, Artist Trust, and Seattle City Artists. She was a runner-up for the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction and a finalist for the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction.