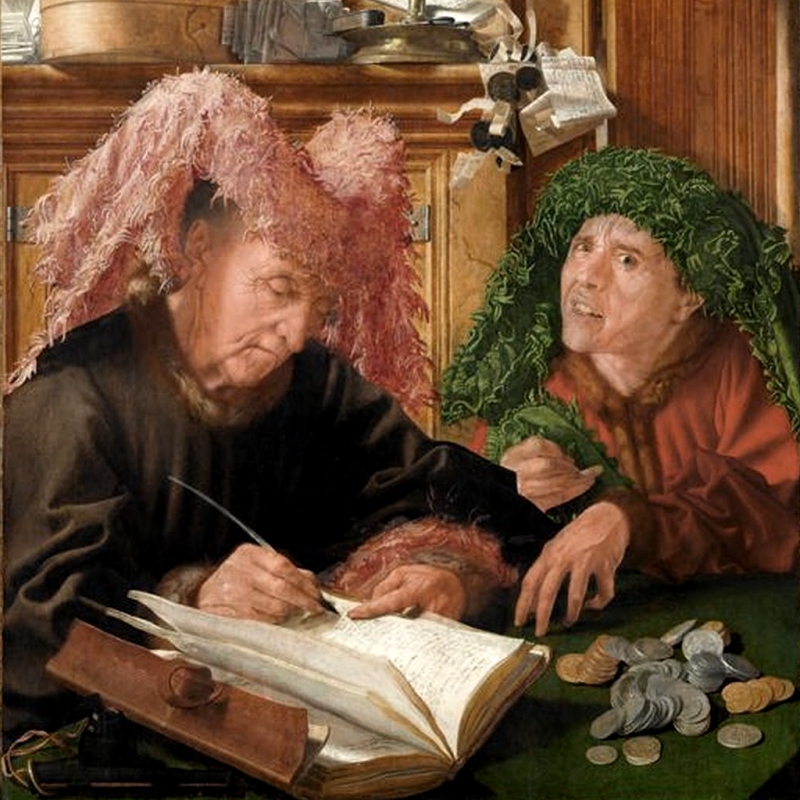

“The Tax Collectors,” oil on panel, by Marinus Van Reymerswaele, c. 1540s.

Last month, my friend (we’ll call her Lisa because she’s shy) wanted to know the most important thing I’d learned about craft. Lisa had recently made the leap of faith to explore her writing talents, and she was taking me up on my open-ended offer to workshop. I held back the first pieces of advice that rushed to mind: Write every day (which I don’t do), show don’t tell, copy Strunk and White’s Elements of Style by hand (which I did do). I wanted something pithy she could feed her muse and grow wings, something I hadn’t read in a book.

“Write until it scares you,” I said. Then I cringed because I realized I’d just quoted Luis Rodriguez.

I tried again. Lisa described well-meaning people who told her she should write about this or that aspect of her life or job, and I worried their demands might stifle her emerging voice. “Unburden yourself of others’ expectations of your writing.” I’d come closer to a maxim suitable for christening her author’s life, but I’d erred telling her what I thought she needed to know. Perhaps it would help her, but it wasn’t what she’d actually wanted.

A small panic crept down my melodramatic spine; I felt as though I were failing as a teacher. In retrospect, we were clearly just two friends talking craft. In the moment, I had to say some profound shit or ruin the future of Lisa’s writing!

“Bad writing is good writing,” I said.

Her eyes reached for politeness, but spilled incredulity. I had come closer to what she’d originally asked me, though, so I pushed on, explained how I’d discovered that bad prose is good. I’d learned this a couple years ago when I’d taken up NaNoWriMo’s challenge to write a novel in a month.

I’m a writer for whom bad prose, stale plot, and flat characters degrade my will to keep writing. It’s distracting in the way that messy workspaces distract compulsively neat people. But when I set about to write a novel in a month, I had to navigate that distraction. Poor writing still drains me, I couldn’t have written 2,000 words a day, while working overtime and attending classes at Patten College’s Prison University Project, without persisting. I knew I’d have to adapt going in, so I committed to writing horribly.

For 30 days, I wrote meandering descriptions of lampposts, indulgent ruminations—whatever kept my fingers moving earned itself a spot on the page. I already knew wretched prose uglies up a page. What I didn’t know: bad writing is clear. Clarity on the page shocked me. What I wanted to say, I said. I didn’t say it concisely, but floating amid swamps of digression were crystal isles of clear intent.

Writing outside my chosen medium relieved the pressure of my own expectations, which relieved the pressure of writer’s block.

Stagnant word swamps entail lots of telling the story rather than showing it. Whatever one says about the inelegance of telling, it’s a clear form of narration. A passage to make the point: “Jack and Jill went up the hill, and Jill giggled because Jack kissed like a trout.” Though this passage doesn’t move me, it presents a clear narrative, and likewise, after writing 50,000 words that read like addresses on cardboard, I had a clear rendering of a novel-length story. In 30 days.

Writers’ processes differ, but here’s my truth: Writing is hard and I hate it; revision is easy, and I want to take it to the movies, then get to third base. I could spend 30 days filling two chapters with pretty paragraphs, but in half that time, I could rework six chapters until nothing but beautiful paragraphs remain. So if you can push through the initial feeling that you suck, bad writing is good because beneath terrible writing, the best words you’ve written wait to emerge. If Lisa carries that on her journey, I’ll be happy.

Although bad writing is good writing proved the best I could muster on the spot, it’s not my most valuable discovery. After Lisa has written pages and pages of horrendous prose (which, with revision, will become pages that fly on her butterfly voice), I’ll tell her the most important thing I’ve learned about craft.

Experiment outside your chosen medium.

Writing outside my chosen medium relieved the pressure of my own expectations, which relieved the pressure of writer’s block. Do you remember the first things you wrote? In grade school, I didn’t get writers’ block. I simply wrote, and teachers got starry-eyed for the awkward kid with ballerina words. I didn’t experience writer’s block until I learned to write “properly.” With knowledge came standards and self-expectation that checked the ballerina words and judged them insufficiently graceful for my vision. Each time I stepped outside of my medium, I entered a sphere wherein I had little knowledge to burden my process. The result: I retained an adult’s acumen, but I wrote with a child’s freedom.

My initial resistance to experimentation had more to do with time than with confidence. True, it scares me to step away from my area of mastery, but like Rodriguez, I’m committed to writing into my fear. Time, on the other hand, has a special hold on me. As a man who’s been serving a life sentence since childhood, I carry a sense that I’ve wasted a life span’s time. To waste any more sets my molars grinding. I thought that whatever time I might spend writing, say, rough poetry, would waste the time I could be using to finish polished fiction. This sense of misspent energy resulted from misunderstanding what experimentation offered me. It took several months of writer’s block for enough desperation to build in me that I became willing to try anything.

When I explored nonfiction, then poetry, I realized I wasn’t wasting my time, because diversifying my craft yielded synergistic benefits. The concision I learned in poetry showed up in my essays. The humor I discovered writing personal essays about difficult subjects emerged in my fiction, and the confidence I’d found in narrative prose infused my poetry.

If writing outside my chosen medium hadn’t strengthened my fiction, I’d still recommend it. We often compare writing to a journey of discovery. We won’t always like what the adventure reveals, but the things we face will make us better, stronger writers—award-winning writers with God-complexes. We might uncover pleasant surprises, that we excel in several mediums, that the writer’s block we experience typing that short story about climate change is in fact our muses telling us a poem would better serve the vision. We might also learn something just as discovering we are literary Da Vincis: what we want to write isn’t necessarily what we’re meant to write.

What we want to write can result from the influences of whom we admire. Admiration provokes imitation, but the writing we dream will crown the New York Times bestseller list demands its own individualized space. It serves us to take a leap of faith away from what we hoped we’d write, if doing so creates the space to accommodate our wings.

Emile DeWeaver is a columnist for Easy Street. His work has appeared or is forthcoming at The Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review, Nth Degree, Drunk Monkeys, and Frigg. He lives and writes in Northern California.